A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern

Health Equity Strategies No. 1

January 27, 2022

Key Learnings

- Many U.S. health-care system features and practices inadvertently contribute to health inequity. Unlike the broad social and economic causes of health inequity, such as poverty and discrimination, the ways in which the health-care system contributes to it can be addressed directly by the system’s participants, including insurers, employers, providers, and the benefit consultants and actuaries who advise them.

- There are six spheres of influence where health-care professionals can take practical steps to improve health equity: insurance and plan design, access, engagement and delivery, incentives, treatment and diagnostics development, and employment policies and practices.

- Meeting the needs of the most vulnerable can improve outcomes for everyone. Health equity should therefore be more than an issue we engage out of a sense of social responsibility. It should also be a primary business objective.

Health equity is the focus of growing attention in the United States, and with good reason. There are large and widening disparities in health expectancy and life expectancy by income and educational attainment, and these in turn are reflected in equally troubling disparities by race and ethnicity. The pandemic has both underscored and exacerbated these inequities. While life expectancy for all Americans fell in 2020, it fell much more steeply for Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks than it did for non-Hispanic Whites.

Most discussions of how to improve health equity focus on addressing the broad social and economic causes of disparate health outcomes, including poverty, discrimination, and unequal access to good schools, decent housing, safe neighborhoods and the other things that allow individuals and families to prosper and thrive. To the extent that the health-care system enters most discussions, it is mainly to note the potential benefits of expanding coverage under government benefit programs. The workings of the health-care system itself, from how health plans are designed to how health services are delivered, are at most an afterthought.

Yet there is considerable evidence that many health-care system features and practices inadvertently perpetuate and perhaps even exacerbate health inequity. The impact of some, such as narrow provider networks, is relatively straightforward, while the impact of others, such as reliance on historical data, average experience, and one-year time horizons in setting practice guidelines and reimbursement rates, is more complex. What all of the ways in which the health-care system contributes to health inequity have in common is that, unlike the broad social and economic causes of health inequity, they can be addressed directly by the system’s participants, including insurers, employers, providers, and the benefit consultants and actuaries who advise them.

The Terry Group plans to publish a series of short issue briefs on health equity over the coming year. The series, which we are calling Health Equity Strategies, will both examine the ways in which the U.S. health-care system contributes to health inequity and suggest actionable responses that could make a meaningful difference. In this inaugural issue, we begin by presenting a schema for thinking about health equity and how it can be improved.

Spheres of Influence and Concern

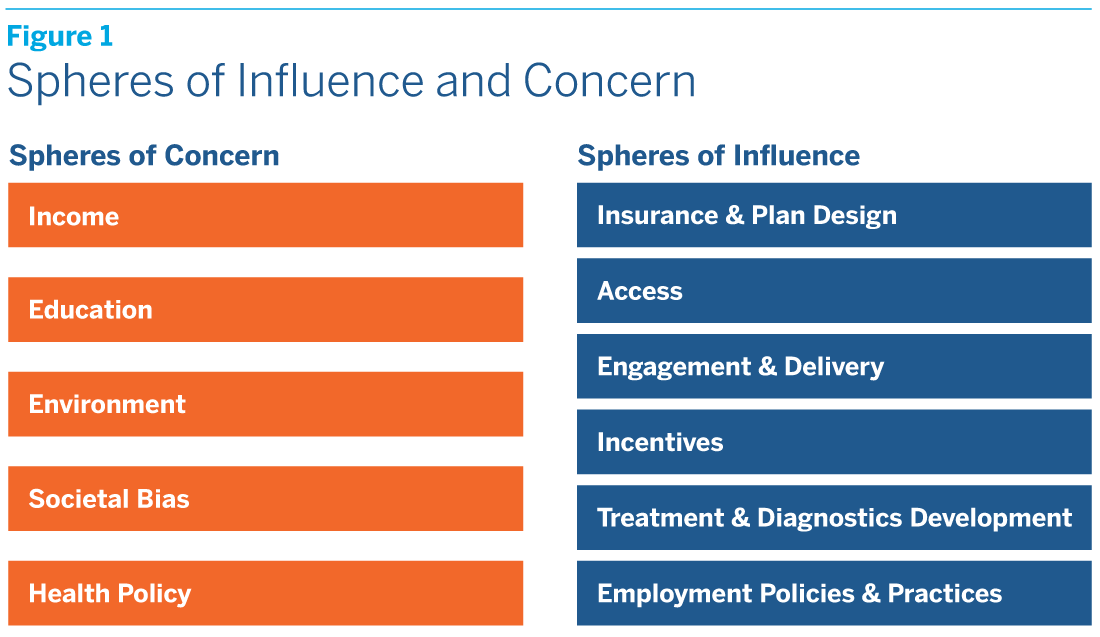

Health equity is generally understood to exist when everyone, whatever their socioeconomic status, race or ethnicity, and gender or age, enjoys the same equal opportunity to realize their full potential to live a healthy life. The persistence of remediable disparities in health outcomes between different groups indicates that society has failed to achieve health equity. In thinking about the reasons that reality falls short of the ideal, it is useful as health-care professionals to distinguish between what we call “spheres of concern” and “spheres of influence.” (See figure 1.)

Spheres of concern encompass the broad social and economic causes of health inequity which, with some important but limited exceptions, we cannot directly address in our capacity as health-care system participants. These spheres include income, education, environment, societal bias, and health policy, here understood as government health policy. Income affects health equity because, without enough of it, people cannot acquire the basic necessities that sustain health. Education affects health equity, both because it is highly correlated with income and because, even independently of income, it is associated with healthier lifestyles. Environment affects health equity because so many key determinants of health, from the quality of public infrastructure to the incidence of violent crime, depend on where we live. Societal bias, whether in the form of racism, sexism, or ageism, affects health equity because it can interact with and reinforce other social and economic conditions that give rise to disparate health outcomes. Health policy affects health equity because restrictive eligibility rules and inadequate reimbursement rates can limit access to the health-care system.

Spheres of influence, on the other hand, encompass the ways in which the health-care system itself contributes to health inequity, which is to say the causes that we can directly address in our capacity as participants. We have identified six spheres of influence: insurance and plan design, access, engagement and delivery, incentives, treatment and diagnostics development, and employment policies and practices. Each of these spheres of influence can in turn be divided into sub-spheres or “domains,” in which specific health-care system features and practices that contribute to health inequity can be identified and actionable responses designed and implemented. For instance, the insurance and plan design sphere is divided into health benefit, non-health benefit, provider network, payment, and medical policy guidelines design domains, while the incentives sphere is divided into patient, provider, and payer incentives domains. (See figure 2.)

A Few Overarching Observations

In subsequent issues, we plan to explore each of the six spheres of influence in detail. Our goal is to identify potential problems, to suggest actionable responses, as well as how and by whom they could be implemented, and to evaluate the obstacles that must be overcome to bring about meaningful change. Here we simply offer a few overarching observations:

- A more expansive understanding of health and health care could improve health equity. Health insurance has traditionally been limited to reimbursing the cost of medical services, without much attention to ensuring that plan members can readily access those services. Something as simple as including transportation to doctor appointments as part of the benefits package could improve health equity for many lower-income Americans. So could crafting health benefits packages that do more to address the nonmedical determinants of health, such as nutrition and lifestyle, since these may have a larger impact on health than medical care. A more wholistic approach to health is critical to improving health equity.

- A more personalized approach to health care could improve health equity. Practice guidelines and protocols are typically based on average clinical experience. While the use of average experience may be appropriate in setting insurance premiums or provider reimbursement rates, health-care delivery should be tailored to the individual. What is statistically true for the population as a whole may not be true for subgroups within the population, much less for a particular individual in any given patient-provider encounter. Health equity could be improved if practice guidelines and protocols took into account not just gender and age, but also race and ethnicity, cultural habits and preferences, and relevant socioeconomic data. It could also be improved if the health education materials provided to individual health-care consumers were similarly personalized.

- A greater focus on long-term outcomes could improve health equity. A central goal of health plan design is to reduce excess utilization, and hence cost. Yet the one-year plan horizon typically used in assessing what is “excess” may fail to capture the long-term benefits of utilization and simply end up pushing health problems and health costs into future years. Similarly, the use of a one-year plan horizon in assessing returns on investment discourages health innovations whose payoffs may be large, but only become apparent over time. Such practices, which are deeply embedded in the health-care system, are likely to have a disproportionate impact on underserved populations.

- A more targeted approach to cost control could improve health equity. Today’s blunt cost control strategies, applied across entire populations, often exacerbate health inequity. The current trend toward narrow provider networks, for instance, may be effective in controlling costs, at least in the short term, but can limit access by creating provider deserts in vulnerable communities. The use of historical utilization data in setting reimbursement rates may also control costs, but to the extent that it builds in past underutilization by disadvantaged populations, it can also exacerbate health inequity. What’s needed are more targeted strategies that control costs without perpetuating health inequity.

- More supportive employment practices could improve health equity. As employers, health-care system participants can also have a direct impact on health equity. To further it, they could increase the wages and enhance the benefits offered to their lower-income and shorter-tenure employees. They could also do a better job of educating all employees about the steps they can take to improve their health and wellbeing across their lifecycle. All of this would help to bridge the gap between spheres of influence and spheres of concern.

A Primary Business Objective

A final word of explanation may be helpful. Although Health Equity Strategies will not directly address the underlying social and economic conditions that give rise to disparate health outcomes, this does not mean that we believe these conditions are immutable. In our capacity as citizens and voters, we can and should seek to bring about positive social and economic change. We recognize, however, that progress may be slow, that there is no national consensus on the types of policies most likely to be successful, and that, as health-care system participants, we have little direct control over the outcome. On the other hand, there are clear, though often overlooked, opportunities to improve health equity by changing the ways in which the health-care system works, and in this we certainly have the capacity to make a difference.

The reason we should seek to improve health equity is first and foremost to right an injustice. But there is another reason as well. From embracing a more expansive understanding of health and health care to adopting a more personalized approach with a greater focus on long-term outcomes, many of the initiatives that would improve health equity would be desirable in any case. Such initiatives would not only allow the health-care system to better meet the needs of the most vulnerable, they would also improve outcomes for everyone. As health-care professionals, whatever our role, health equity should therefore be more than an issue we occasionally engage out of a sense of social responsibility. It should also be a primary business objective.