America’s Looming Fiscal Crisis

Vantage Point: Mini Briefs from The Terry Group and the Global Aging Institute

April 9, 2025

According to the CBO, large chronic budget deficits will push the national debt up to 156 percent of GDP by 2055, a level once associated with banana republics. In this Vantage Point, we offer an overview of the long-term budget outlook and the dangers it poses. We also explain why, as daunting as they are, CBO’s projections may greatly understate the magnitude of America’s looming fiscal crisis.

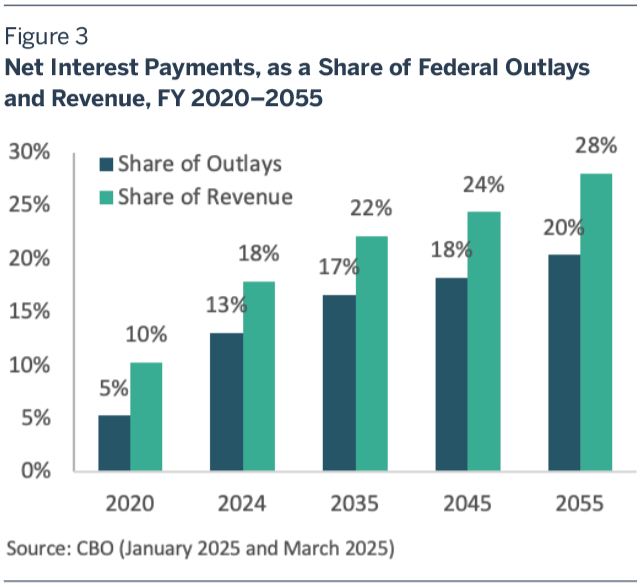

The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) latest Long-Term Budget Outlook, released in March, confirms that U.S. fiscal policy remains on a dangerously unsustainable course. According to the CBO, large chronic budget deficits will push the national debt up to 156 percent of GDP by 2055, a level once associated with banana republics. By then, America will be spending twice as much each year on interest payments to bondholders as it will be on national defense.

In this Vantage Point, we offer an overview of the long-term budget outlook and the dangers it poses. We also explain why, as daunting as they are, CBO’s projections may greatly understate the magnitude of America’s looming fiscal crisis.

Some Budget Basics

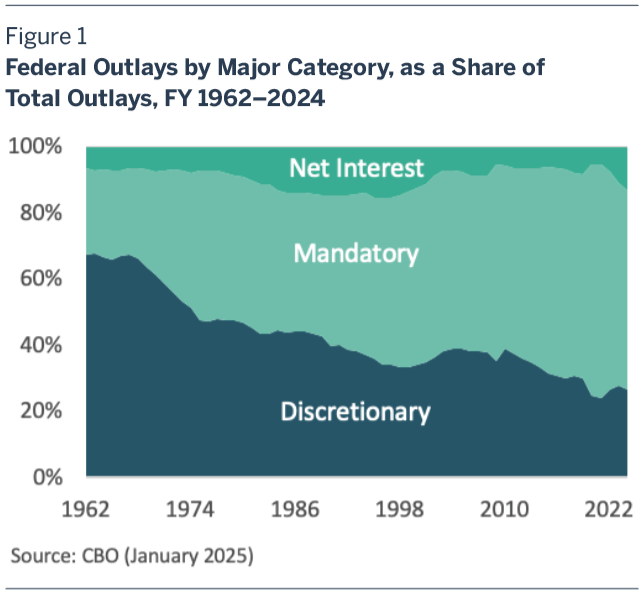

Before turning to the projections, it may be helpful to review some budget basics, starting with the difference between discretionary spending and mandatory spending. It is the first that is the focus of current budget-cutting efforts, but it is the second that, along with net interest payments, is driving up federal outlays.

Discretionary spending is spending that Congress must vote on each year. One might think that such spending would constitute the great majority of federal spending, but in fact it made up just 27 percent of the total in 2024. Its relatively small size notwithstanding, discretionary spending is what pays for most of the core functions of government, from the Pentagon to Homeland Security and the National Institutes of Health.

While discretionary spending must be voted on each year, mandatory spending runs on autopilot so long as the statutes which authorize it remain in force. All of the major entitlement programs fall into the mandatory spending category, including Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Indeed, they are entitlements precisely because they are mandatory. In 2024, mandatory spending made up 60 percent of total federal spending.

The relative weight of discretionary and mandatory spending in the budget has shifted dramatically over the postwar era. As recently as the 1960s, most federal spending was discretionary, and thus subject to annual review by Congress. Today, due to program expansions, the aging of the population, and rising health-care costs, mandatory spending has come to dominate the federal budget. (See figure 1.)

There is of course a third broad category of federal spending: net interest payments. Like entitlement benefits, they are mandatory. There is, however, an important difference between payments to federal beneficiaries and payments to federal bondholders. Congress can reduce the former by changing the program rules. It cannot reduce the latter short of defaulting on the national debt. In 2024, net interest payments made up 13 percent of total federal spending.

In recent decades, federal tax revenue has fallen chronically short of covering federal outlays. The difference between outlays and revenue is of course the federal deficit, which must be financed by borrowing from the public. The fact that America now runs chronic budget deficits may seem like a purely financial problem, but it also reflects a deeper problem of political economy. America runs chronic budget deficits because Americans want more from the government than they are willing to pay for.

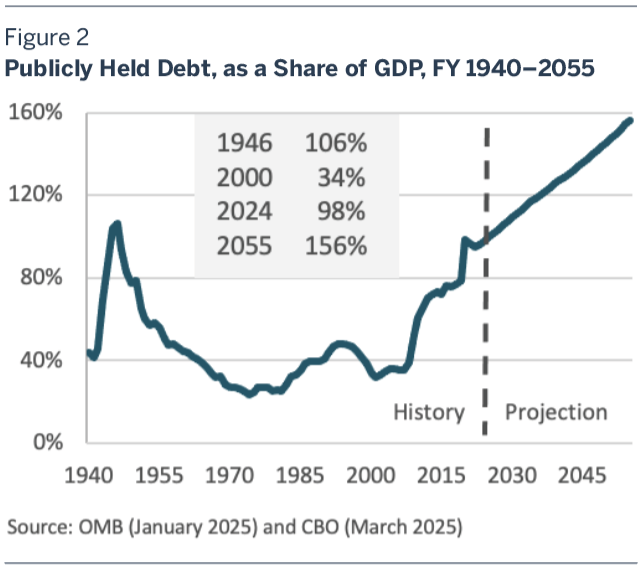

Over the past twenty-five years, the federal deficit has averaged 4.6 percent of GDP. In 2024, it was 6.4 percent of GDP, higher than at any time over the course of the entire postwar era except for 2009–2012 in the wake of the Great Recession and 2020–2021 in the midst of the pandemic. At the end of 2024, the publicly held debt, which is the cumulative sum of prior year deficits, totaled 98 percent of GDP, triple its level twenty-five years ago and just shy of its all-time historical high of 106 percent of GDP, registered in 1946 at the end of World War II.

A Persistent Mismatch

Each year, the CBO publishes ten-year budget projections that have long served as the official baseline for Congress in its fiscal deliberations. Each year, it also publishes long-term projections that extend its official baseline for an additional twenty years. The long-term projections released in March thus have a time horizon of 2055.

These projections should be a wake-up call. According to CBO’s extended baseline, deficits will average 6.3 percent of GDP over the next thirty years. Along the way, this persistent mismatch between revenue and outlays will drive up the publicly held debt to 118 percent of GDP in 2035, the end of the ten-year budget window. The debt will then keep rising, all the way to 156 percent of GDP in 2055. (See figure 2.)

As difficult as it may be to believe, this is probably a best-case scenario. The CBO projects that mandatory spending, driven mainly by growth in Social Security and Medicare, will increase by 2.1 percent of GDP from 2025 to 2055. It also projects that net interest payments will increase by 2.2 percent of GDP, growing to 20 percent of total federal outlays and 28 percent of total federal revenue by 2055. (See figure 3.) The deficit impact of all of this extra spending, however, is largely offset by a projected decline of 1.0 percent of GDP in discretionary spending and a projected increase of 2.2 percent of GDP in federal revenue.

The first of these offsets is far from guaranteed. Since discretionary spending is appropriated annually, no one knows what it will be in three years time, much less in thirty. Projecting it therefore requires making some ad hoc assumption about its future growth. The prudent approach would be to assume that discretionary spending grows at the same rate as GDP. And in fact, beyond 2035, this is precisely what the CBO assumes. Over the next ten years, however, budgetary rules require the CBO to assume that discretionary spending merely grows with inflation, thus shrinking as a share of GDP. This may happen. Then again, given the proliferation of unmet domestic needs and geopolitical challenges, it may not.

As for the second offset, we already know that it is in large part illusory. The CBO is required to project federal revenue based on current law, regardless of whether current law is likely to be lasting. In accordance with this requirement, it assumes that the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) will expire on schedule at the end of 2025, even though Congress is about to make them permanent. According to the CBO, extending the TCJA’s major provisions would alone push the publicly held debt to over 200 percent of GDP by 2055.

Two Grave Dangers

The current direction of U.S. fiscal policy poses two grave dangers that ought to be of concern to all Americans, whatever their political leanings.

The first danger is that it puts the federal budget in a straitjacket. As time goes by and a larger and larger share of the budget is devoted to honoring past spending commitments to beneficiaries and bondholders, our elected officials find it harder and harder to respond to new challenges and pursue new agendas. In effect, to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, our fiscal choices are no longer our own to make, but are dictated by the dead hand of the past.

The second danger is that it risks undermining economic and living standard growth. For roughly a decade following the Great Recession, ultra-low interest rates seemed to make any amount of federal borrowing affordable. Indeed, some adherents of a heterodox school of economic thought called Modern Monetary Theory even argued that not to borrow hand over fist amounted to fiscal malpractice. As we enter what looks to be a lasting new era of higher interest rates, we may come to rue this recklessness.

It’s not just that soaring interest payments will crowd spending on other priorities, including public investment, out of the federal budget. Unchecked government borrowing could also crowd private-sector investment out of capital markets, fuel inflation, and put further upward pressure on interest rates.

The endgame could be ugly. If bondholders lose confidence in the sustainability of U.S. fiscal policy or come to suspect that the government will tolerate higher inflation in order to erode the value of the national debt, they may begin to dump Treasuries. Since U.S. government debt plays a critical role in the stability of the international financial system, a large-scale selloff could trigger a global financial crisis. It could also trigger a domestic fiscal crisis if the federal government is forced to suddenly enact large tax hikes or large spending cuts, perhaps in the midst of a severe economic downturn.

Yes, there are some who continue to believe that the growing national debt poses no real cause for concern. In their view the United States, as issuer of the global reserve currency and ultimate investment safe haven, will always be able to borrow as much as it needs in financial markets.

Perhaps. But at a time when the global economic and geopolitical landscape is shifting as rapidly as it now is, do we really want to bet our children’s future on the assumption that the United States will indefinitely enjoy the same privileged borrowing status that it does today? The global financial system may be structured very differently ten years from now, much less thirty. Indeed, it seems increasingly likely that it will be.

Herb Stein’s Wisdom

The late economist and sometime humorist Herb Stein is reputed to have said that things which are unsustainable tend to stop. When it comes to America’s deficit-financed experiment in free-lunch economics, the only question is when and how. Will the course correction be made with forethought, giving people time to adjust and prepare? Or will it come suddenly in the midst of crisis?

Unfortunately, the utter lack of fiscal seriousness among today’s political leaders suggests that the landing may be a hard one. One side pretends that rooting out waste, fraud, and abuse in the tiny discretionary corner of the federal budget will somehow right America’s listing fiscal ship, while the other pretends that raising taxes on the tiny sliver of households in the top income bracket will do the job.

Almost no politician is willing to acknowledge what every budget analyst who has looked carefully at the numbers understands. There is simply no way to stabilize the national debt as a share of GDP, much less to balance the budget, without enacting some combination of broad-based tax hikes and broad-based entitlement cuts. It would be nice if there were another option. Alas, simple arithmetic dictates otherwise.