How Biased Utilization Data Perpetuate Health Inequity: A Two-Part Strategy to Address the Problem

Health Equity Strategies No. 2

May 17, 2022

Key Learnings

- Utilization data play a central role in steering health-care financing and delivery. When, due to underutilization and misutilization, the data do not accurately reflect the underlying health needs of disadvantaged populations and communities, it can lead to a serious misallocation of health-care resources that perpetuates health inequity.

- The Terry Group proposes a two-part strategy to address the problem. The first part involves what we call “informed leaps of faith” in which insurers, health systems, provider groups, or large employers would proactively launch initiatives designed to improve engagement with the health-care system in communities where observation, experience, and available SDOH data suggest that health needs are greater than the utilization data indicate.

- The second part of the strategy involves in-depth community studies designed to identify the underlying causes of underutilization and misutilization. The observational and survey data collected in these studies would be used to refine the leap-of-faith initiatives already under way in at-risk communities, retrain predictive health algorithms, and, through integration into individual medical records, improve patient and member outreach and engagement. All of this would in turn help to reduce inappropriate utilization and increase appropriate utilization.

- The goal of the first part of the strategy is to offset the adverse impact of biased utilization data on health equity. The goal of the second part is to eliminate that adverse impact by, over time, improving the utilization data itself. Along with the health benefits for individuals, there would also be financial benefits for payers and providers.

In the first issue of this series, we argued that many U.S. health-care system features and practices inadvertently perpetuate and may even exacerbate health inequity. Unlike the broad social and economic causes of health inequity, from poverty to discrimination, these problems can be addressed directly by the system’s participants, including insurers, employers, providers, and the benefit consultants and actuaries who

advise them.

One of the most significant problems involves reliance on historical utilization data. Utilization data are used for a wide variety of purposes in the health-care system, including establishing provider networks, setting negotiated reimbursement rates, and calculating risk adjustment scores. They are also fed into the predictive health models used to target preventive care services to at-risk patients and plan members and to prioritize case management outreach.

The problem is that the data may not accurately reflect the underlying health risks and needs of underserved populations. To begin with, insurance coverage is skewed by socioeconomic status, as well as by race and ethnicity, with Blacks and Hispanics less likely to have coverage than non-Hispanic Whites. Even when people have coverage, moreover, members of disadvantaged groups in the population may face barriers to utilization that members of more advantaged groups do not. And when members of disadvantaged groups do interact with the health-care system, it is more likely to be in the ER, which means that standard health assessment data are often not collected.

Since utilization data play such a central role in steering health-care financing and delivery, bias in the data can lead to a serious misallocation of health-care resources that perpetuates health inequity. Nor is this merely a hypothetical concern. A growing number of studies have confirmed that utilization data often significantly underestimate the underlying health needs of minorities.1

That historical utilization data may not accurately reflect underlying health risks and needs is hardly news to most of the insurers, providers, and other health-care system participants who use it. However, the use of utilization data is deeply ingrained in the health-care system, and there appears to be no real alternative to relying on it.

We propose a two-part strategy to address the problem. The first part involves what we call “informed leaps of faith” in which insurers, health systems, provider groups, or large employers would proactively launch initiatives designed to improve engagement with the health-care system in communities where observation, experience, and available social determinants of health (SDOH) data suggest that health needs are greater than the utilization data indicate.

The second part of the strategy, which would be undertaken concurrently with the first, involves in-depth community studies designed to identify the underlying causes of underutilization and misutilization. The observational and survey data collected in these studies would be used to refine the leap-of-faith initiatives already under way in at-risk communities, as well as to retrain the algorithms insurers and other health-care system participants use to predict health risks and needs. The data collected at a community-wide level could also be collected from individual patients and plan members and integrated into their medical records in order to personalize engagement. All of this would in turn help to reduce inappropriate utilization and increase appropriate utilization.

This two-part strategy would help to improve health equity in both the near term and long term. The proactive initiatives in at-risk communities envisioned in the first part would immediately help to offset the adverse impact of biased utilization data on health equity by increasing appropriate engagement with the health-care system. The insights gained from the in-depth community studies envisioned in the second part would allow for the personalization of patient outreach, further increasing appropriate engagement. Over time, the utilization data on which health-care system participants rely would become more representative, leading to a more equitable allocation of overall health-care resources and additional improvements in health equity.

Along with the health benefits for individuals, there would also be financial benefits for payers and providers. The potential to realize significant returns on investments in health equity is obviously greatest in value-based payment systems, where improvements in health translate directly into improvements in the bottom line. But there are also significant opportunities to realize positive returns in fee-for-service payment arrangements.

The next section explains in more detail how the use of biased historical utilization data can perpetuate health inequity. The two sections that follow turn to the proposed two-part strategy for addressing the problem. The final section offers some thoughts on how to overcome the obstacles that may stand in the way of implementing the strategy.

The Biased Data Problem

Historical utilization data play a critical role in steering many aspects of health-care financing and delivery. When the data fail to reflect underlying health risks and needs, their use can therefore lead to resource misallocation and undermine health equity through multiple channels. Among the most important are:

- Provider Networks. When utilization data do not reflect underlying health risks and needs, provider networks may not be established in certain communities, or if they are established may not have the right mix of primary care physicians, specialists, and other health-care professionals.

- Benefit Design. When utilization data do not reflect underlying health risks and needs, plan benefit design may fail to address the special needs of underserved populations, including nonmedical needs such as nutrition and transportation assistance.

- Community Outreach. When utilization data do not reflect underlying health risks and needs, it may result in less community outreach, making it more difficult to meet the health needs of vulnerable patients and plan members, worsening eventual health outcomes and increasing eventual health-care costs.

- Member Enrollment. Lack of community outreach can also result in lower plan enrollment, leaving the health needs of the wider community unmet, once again worsening eventual health outcomes and increasing eventual health-care costs.

- Preventive Care Services. When clinical indicators are missing from patients’ records due to underutilization or misutilization, models designed to predict the onset of disease and target preventive care services may overlook at-risk patients and plan members, with adverse implications for both health and cost outcomes.

- Case Management. When clinical indicators are missing from patients’ records due to underutilization or misutilization, models designed to prioritize case management services may also overlook at-risk patients and plan members. The same is true of models designed to predict the likelihood of hospitalization or failure to adhere to treatment and medication regimens.

- Risk Adjustment. When underutilization takes the form of missed Annual Wellness Visits (AWVs), it may result in understated risk adjustment scores, leading to less funding for payers and providers. This in turn can further undermine the quality of care for underserved populations, exacerbating underlying health problems and/or pushing utilization into inappropriate (and more expensive) settings like the ER.

Informed Leaps of Faith

For both moral and economic reasons, payers and providers need to address these problems. Taking the first steps without representative utilization data as a guide will require leaps of faith. However, they need not be blind ones.

There are of course national data on the incidence of chronic health conditions by age, gender, and race and ethnicity. There are also data on SDOH variables at the community level. Based on these data, as well as observation and experience, payers and providers could make informed guesses about those populations and communities that are most likely to be underserved. After taking into account existing community health resources and the possibility of partnerships with community-based NGOs, they could also design and implement a wide variety of initiatives that could have a large impact on engagement, and hence health equity. Among the possibilities are:

- Community Center Clinics. Health systems and provider groups looking to expand access channels for underserved populations could establish clinics at community centers. A wide range of services could be provided, including AWVs. Bringing health-care services to where community members already are, as opposed to requiring them to come to you, will increase appropriate utilization of health-care services and result in better health outcomes. It also has the potential to improve finances in both value-based and fee-for-service payment arrangements.

- Mobile Health Units. Health systems, provider groups, and large employers could employ mobile health units to bridge gaps in preventive care services in targeted neighborhoods. Such units may not be capable of performing more complicated or sensitive procedures, such as breast cancer or colorectal screenings. But they could provide vaccinations, take blood pressure readings, make blood draws, and set up appointments for additional screening at the most conveniently located health facility.

- Food as Medicine Programs. Insurers, health systems, provider groups, and large employers could create food as medicine programs for targeted geographies where nutritional needs are high and nutrition-related education is low. Such programs can help prevent, manage, and treat illness. They also provide opportunities for dieticians and case workers to have regular interactions with patients that may suggest the need for additional health interventions.

- Nonmedical Benefits. Insurers and large employers could offer transportation reimbursement benefits to remove what is often a major barrier to access for underserved populations. In the same vein, health systems and provider groups could provide shuttle services for nonemergency health visits, as well as to meet additional patient needs such as prescription or grocery pickups. Insurers and large employers could also offer childcare benefits to remove another important barrier to access, while health systems and provider groups could provide back-up childcare services on site.

- Community Health Training Programs. Health systems and provider groups could create programs to train community health workers and patient navigators, who would be tasked with identifying unmet needs in the community and referring people to appropriate medical and nonmedical resources.

Asking the Right Questions

While initiatives such as these will make important contributions to improving health equity, they are admittedly blunt instruments. To refine them, as well as to make targeted interventions at the individual as opposed to the community level, it is necessary to understand exactly what is driving the underutilization and misutilization of health-care services.

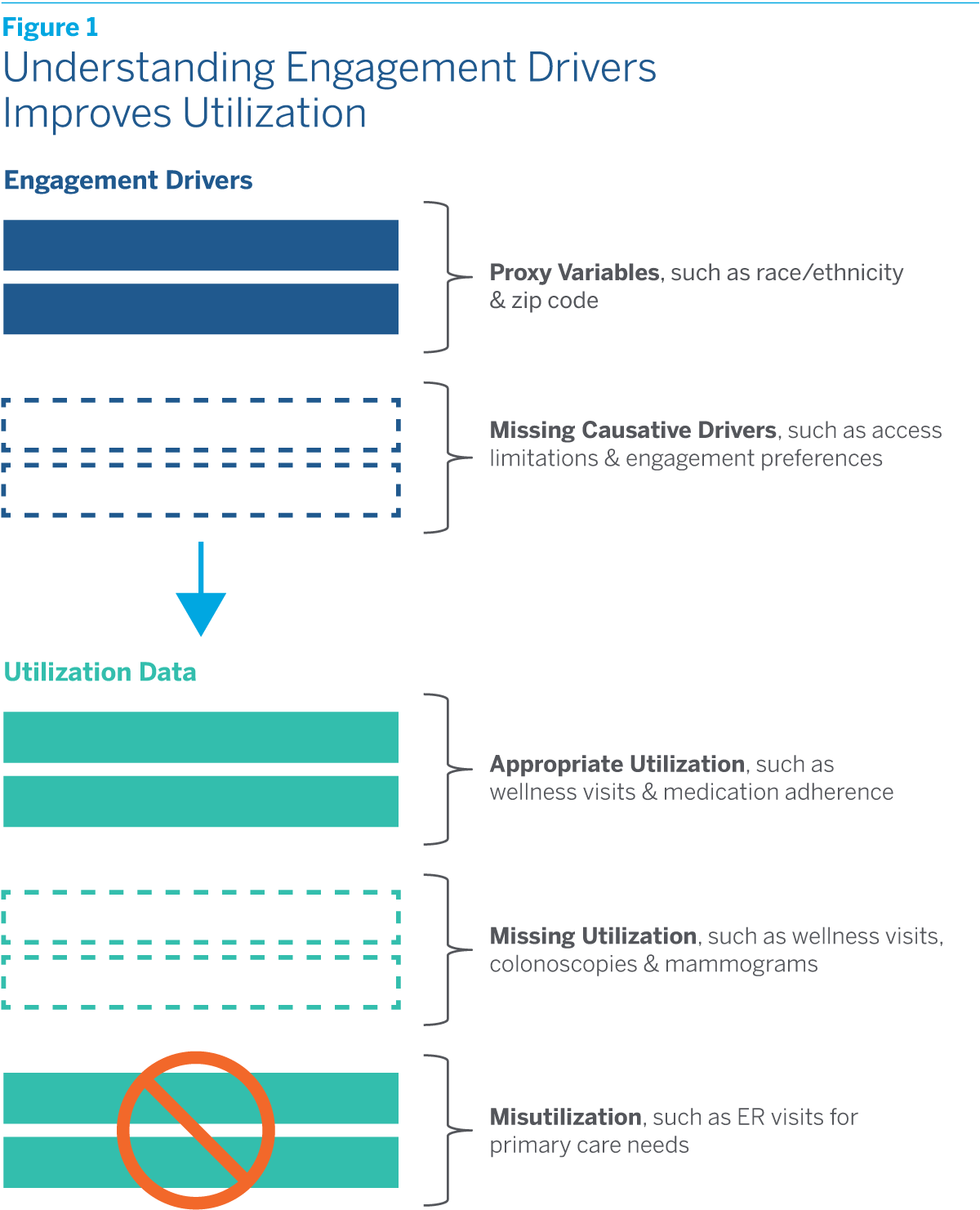

Knowing the racial and ethnic mix in a community, as well as how it ranks in terms of such SDOH variables as income, the quality of schools, or the crime rate, is of course helpful. Knowing the race, ethnicity, educational attainment, and zip code of individual patients and plan members is also helpful. But ultimately these variables are merely proxies for the deeper underlying obstacles to engaging, or appropriately engaging, with the health-care system that underserved populations often face. They are correlated with the underutilization and misutilization of health-care services, but are not necessarily the causes.

To understand individual behavior we must drill down deeper. Perhaps it is lack of trust in the health-care system that prevents some people from engaging with it. Perhaps it is caregiving responsibilities that prevent others. Or maybe the reasons lie in language barriers or unmet transportation needs. Such questions cannot be answered, or at least not fully answered, by proxy data on the demographic or socioeconomic group to which people belong or the community in which they live. We call these underlying determinants of individual behavior causative engagement drivers to distinguish them from proxy variables.

Identifying which causative drivers are the most important will require in-depth community studies. As we envision them, these studies would begin with an exploratory phase in which information and data related to the lived experiences of people in the community are gathered through extensive observation and interviews with key community actors. Based on what is learned, a survey instrument would then be designed with the goal of identifying “sustainable pathways” through which patient behavior can be influenced.

To be successful, studies of this kind would have to be carried out in close partnership with one or more NGOs with deep roots in the community. They would also have to make use of trusted messengers, such as community health workers or peer navigators, during both the exploratory phase and the fielding of the survey.

The particular questions that would be asked in a given community would of course depend on the insights gained during the study’s exploratory phase. But based on our review of the health equity literature and own professional experience, we believe that focusing on the following areas might yield fruitful results:

- Attitudes toward the Health-Care System. Underlying attitudes toward the health-care system help to determine the way people engage with it. Trust is critical to engagement. Yet some members of the community may have a low level of trust in the system because they perceive it as unresponsive or racist based on historical injustices or their own experiences. An understanding of the ongoing role that the system can play in monitoring and maintaining health is also critical to engagement. Yet some members of the community may view visiting the doctor solely as something you do when you get sick, rather than something you do to stay well. Understanding these attitudes can improve both engagement and outcomes.

- Competing Priorities. Everyone must juggle competing priorities in life, but doing so can be especially challenging for members of disadvantaged populations, who may have limited financial resources and limited support networks. Caregiving responsibilities may keep people from making or keeping doctors’ appointments, as well as deprive them of the personal time needed to maintain their own health through proper diet and exercise. So can job demands, especially if people must hold more than one job to make ends meet or employers do not provide for paid personal leave. Understanding these constraints can help providers better target patient outreach.

- Access Limitations. Public transportation to and from doctors’ appointments may be inconvenient or unavailable in some communities, and the alternatives may be unaffordable for some patients. People may also have limited access to healthy food, as well as to parks, walking and biking trails, and fitness facilities. Understanding these access limitations can help to increase patient engagement, improve predictive health models, and better target preventive care services.

- Financial Insecurity. Financial insecurity can affect both health and engagement with the health-care system. Although people might not be willing to share information about their income and assets, a survey could certainly ask them whether they have a checking or savings account; whether they own or rent their home; whether they have left a prescription unfilled in the prior year due to lack of money; whether they could afford an unexpected expense of, say, $500; or whether they are saving for retirement. Just like information about access limitations, information about financial insecurity is critical to assessing health risks and needs.

- Engagement Preferences. Meeting people’s health needs requires knowing their engagement preferences. What is their primary language? What is their preferred communication channel? Can they schedule weekday appointments or are evening or weekend appointments essential? Are telehealth visits an option? When engagement is driven by providers’ preferences rather than patients’, as is too often the case, the result is less engagement.

- Personal Health Risks. Many factors that contribute to poor health outcomes, from substandard housing to substandard schools, are community-related, and so can be inferred from available SDOH data. To more fully understand the health risks that people face, however, information about these environmental risks needs to be supplemented by information about specific personal risks, from occupational hazards to risky lifestyle behaviors. The only practical way to learn about these is to ask the individuals in question.

- Health Awareness. Awareness about available health resources is a critical determinant of engagement with the health-care system. The survey should therefore probe people’s knowledge about their eligibility for government health programs like Medicaid and CHIP, as well as enrollment cycles and the types of services covered. It should also probe their knowledge about other health-related resources in the community, from food banks to free clinics. Awareness about one’s own health is an equally important determinant of engagement with the health-care system. The survey should therefore ask people to report their health risks and needs, as they understand them, as well as whether and how they are addressing them.

The observational data gathered during the exploratory phase of these community studies, together with the data obtained from surveys of this kind, could improve health equity in several ways. Naturally, the data could be employed to refine leap-of-faith initiatives that are already under way in at-risk communities as well as to develop new ones. The data could also be employed to retrain the algorithms used to predict health risks and needs, which now must rely on biased utilization data.

The greatest benefits, however, would likely come from applying the insights gained from community studies to individual patients. This could be done by asking patients and plan members those survey questions which yielded the most valuable information about obstacles to engagement in the community. The responses would then be integrated into patient medical records with a view to personalizing engagement. Insurers could perhaps collect some of the data during the enrollment process. Providers could certainly collect much or all of it during patients’ AWVs. For patients who miss these visits, there could be a special outreach process in which the data are collected via phone calls, telehealth visits, or even at-home visits. Casting the net still wider, data collection points could be set up in other medical settings, such as the ER, or nonmedical settings, such as community centers.

We believe that the integration of data on engagement drivers into patient medical records will reduce inappropriate utilization and increase appropriate utilization. Figure 1 offers a schematic depiction of the process. Engagement drivers are shown as rows at the top of the schematic, while utilization data are shown as rows at the bottom. As the missing engagement driver rows are filled in and outreach and engagement improve, missing appropriate utilization rows will also fill in and inappropriate utilization rows will drop out. Over time, the utilization data so crucial to allocating resources within the health-care system will improve. And as the allocation of health-care resources improves, so will health equity.

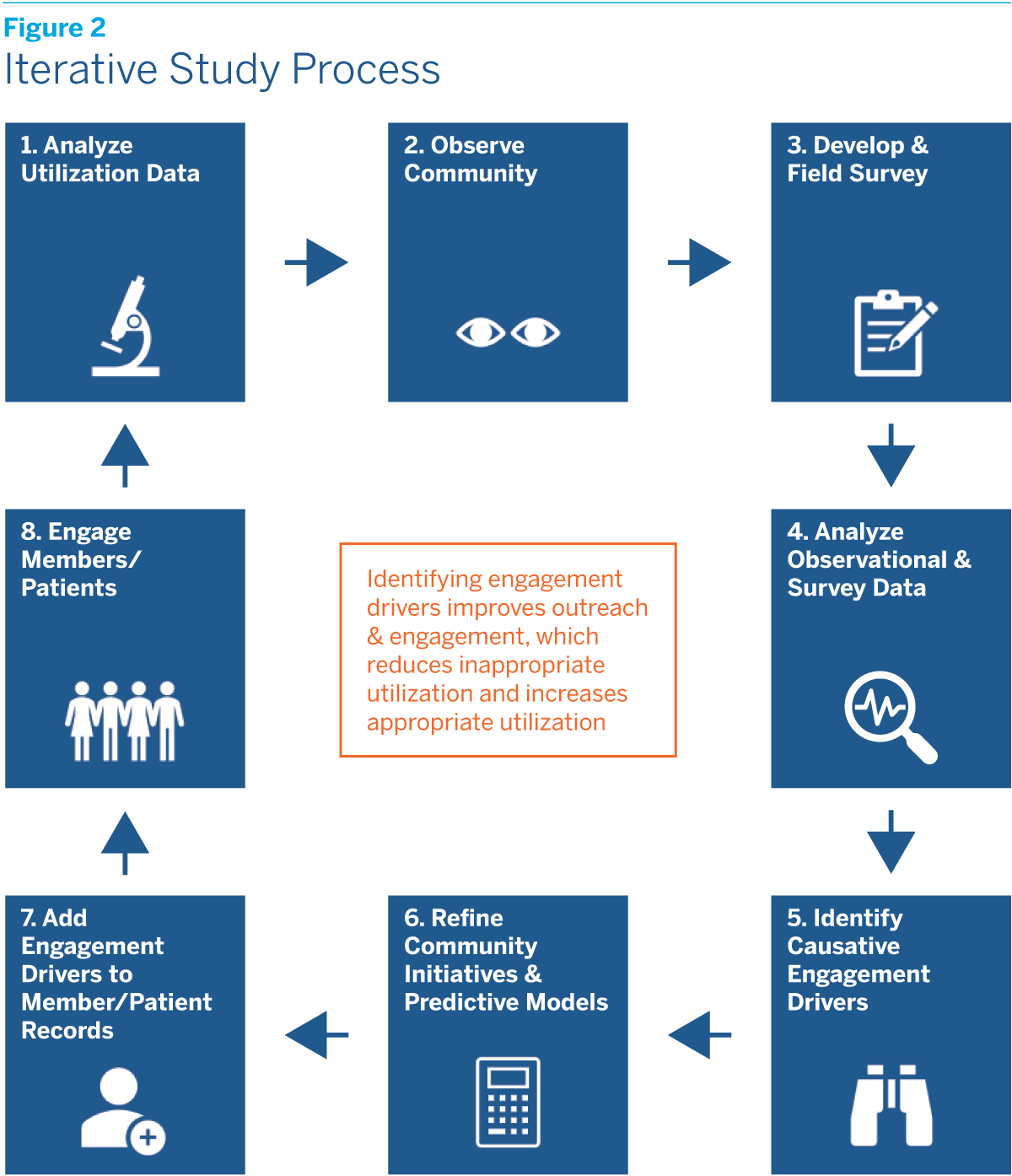

This will not happen overnight. A successful study will need to be an iterative process in which utilization data are analyzed, observational and survey data are collected, causative engagement drivers are identified and integrated into patient medical records, stepped-up patient outreach and engagement occur, the impact on utilization is analyzed, and the whole process is repeated. Figure 2 offers a second schematic depicting this iterative process. While a successful study will require a significant commitment of time and money, the results could be life-changing for underserved populations and communities.

Meeting the Challenge

If this strategy is to succeed it will need to overcome many challenges. To begin with, there will have to be high-level support within any organization that decides to undertake it. Securing the buy-in of relevant corporate officers and ensuring system-wide coordination across different departments and sites is critical. Identifying and engaging board members who see improving health equity as part of their fiduciary mandate will also be helpful. Along with sufficient financial and human resources to pursue the strategy, there needs to be a long-term vision and a long-term commitment.

It is equally important to build relationships with committed external partners. These partners might include nonprofit foundations, which could collaborate in designing leap-of-faith initiatives and in-depth community studies, as well as provide funding. They would certainly include NGOs operating in the community, as well as other community actors ranging from childcare providers to pharmacies and food delivery services. All of these partners will need to be carefully researched to ensure not only that they possess the relevant capabilities, but also that they are trusted in the community.

The organization should recognize that many of these partnerships will need to be ongoing ones. While it is critically important that payers and providers better understand the special nonmedical needs that may affect utilization in a community, they cannot substitute for community service organizations in addressing all of those needs.2 The goal should be to cooperate with them more effectively, whether through referrals or “hot handoffs.” There will also need to be mechanisms that allow diverse voices in the community to be heard, such as patient or neighborhood advisory councils.

A successful strategy will require conducting research on the legal and regulatory constraints related to information collection and sharing. Even apart from these constraints, privacy concerns must be scrupulously respected in order to overcome the possible hesitancy of community members to participate in the survey or of patients to have sensitive personal information incorporated into their medical records.

Finally, a successful strategy will have to demonstrate a positive return on investment. In health terms, ROI will need to be measured by tracking improvements in outcomes. In financial terms, it will need to be measured by tracking the savings from, for instance, reductions in ER visits and hospital admissions and readmissions. While the long-term ROI on both fronts is likely to be both positive and large, it may not be possible to demonstrate this at the planning stage. Indeed, since improvements in health and the associated savings accrue over many years, it may not be possible to demonstrate it over the typical one-year plan horizon.

The uncertainty surrounding near-term ROI may be an insurmountable obstacle for some organizations. But for others, the opportunity to make real improvements in health equity, combined with the prospect of longer-term savings, will be a compelling reason to act.

We will return to the subject of ROI in the next issue of Health Equity Strategies, which will explain in greater detail why advancing health equity is not just a moral imperative, but also a financial one. Stay tuned.

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern