The Coming Social Security Trainwreck

Vantage Point: Mini Briefs from The Terry Group and the Global Aging Institute

June 26, 2025

According to the latest report of the Social Security Trustees, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund will be depleted in 2033, effectively triggering an immediate 23 percent benefit cut. In this Vantage Point, we offer a brief summary of the Trustees’ findings. We also provide some essential background on how trust-fund accounting works and how Social Security’s financial status is measured.

The Social Security Trustees released their 2025 annual report last week. As expected, the bottom line is stark. The Trustees project that the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund, which pays for retirement benefits, will be depleted in 2033, effectively triggering an immediate 23 percent benefit cut if Congress fails to take remedial action before then. OASI’s actuarial deficit, a summary measure of the program’s funding shortfall, now weighs in at 3.95 percent of taxable payroll, double what it did just fifteen years ago.

That Social Security faces a funding shortfall is hardly news. The Trustees have been warning for years that action is urgently needed to shore up the program. Still, the release of the new Trustees’ report provides a useful occasion to refocus attention on this critical issue. In this Vantage Point, we offer a brief summary of the Trustees’ findings. We also provide some essential background on how trust-fund accounting works and how Social Security’s financial status is measured.

The Arcana of Trust-Fund Accounting

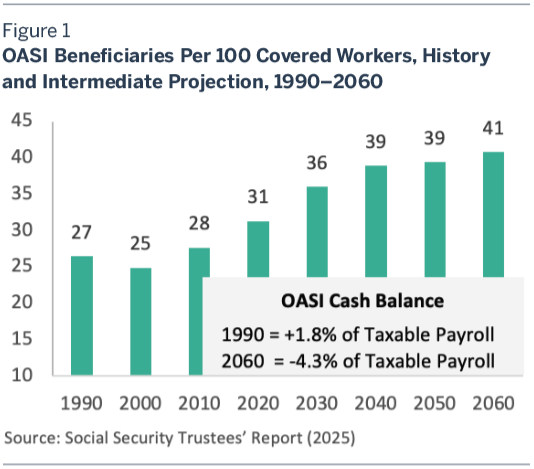

The root cause of Social Security’s financial difficulties is straightforward enough. The number of retired beneficiaries is growing more rapidly than the number of contributing workers, which in turn means that program expenditures are growing more rapidly than program tax revenue. (See figure 1.) This imbalance is mainly the result of the aging of the U.S. population, which is driven by declining birthrates, increasing life expectancy, and the retirement of the unusually large baby boom generation.

The reason that Social Security must cut OASI benefits in 2033 is more complex and involves the arcana of trust-fund accounting. Many federal programs are financed through trust funds, some small and some large like Social Security’s. Unlike private trust funds, whose assets are invested in financial markets, federal trust funds are simply accounting devices that the government uses to keep track of earmarked tax revenue and associated program expenditures. When earmarked tax revenue exceeds program expenditures, Treasury issues IOUs to the trust fund in the form of special nonmarketable securities. When program expenditures exceed earmarked tax revenue, the trust fund can redeem those securities to pay benefits. The IOUs thus represent an asset to the trust fund but a liability to Treasury.

Trust-fund accounting has several potential advantages for a benefit program like Social Security. At least in theory, it ensures that the program is self-financing, and this helps to reinforce popular support for it. Since program expenditures by law cannot exceed earmarked tax revenue if the trust fund is depleted, it may also help to foster fiscal discipline and encourage timely reform. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, trust-fund accounting allows Social Security to partially prefund benefits.

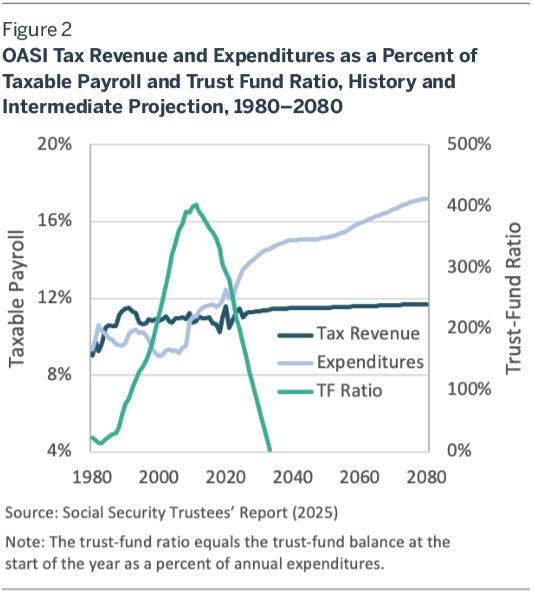

This brings us to the trust-fund buildup and drawdown that has ensured Social Security’s solvency over the past few decades. Back in 1983, the last time the OASI trust fund faced imminent depletion, a landmark reform package raised FICA taxes well above the “pay-as-you-go” rate that would have been needed to pay current benefits at the time. In addition, benefits were for the first time subject to income taxes, with the proceeds earmarked for the trust fund. The result was a large trust-fund buildup that partially prefunded the baby boom’s retirement. On a cash basis, Social Security has been running widening deficits since 2010. Its trust fund, however, has covered the shortfall. (See figure 2.)

Whether Social Security trust-fund assets constitute genuine economic savings is debatable. The answer depends on whether the surpluses that Social Security ran during the trust-fund buildup reduced the unified budget deficit, thus increasing national savings, or whether they simply allowed the federal government to spend more or tax less than it otherwise would have, leaving national savings unchanged. If it is the latter, the trust-fund buildup may have extended Social Security’s solvency, but it did nothing to alleviate the fiscal and economic burden of financing the program.

However one interprets the economics of the trust-fund buildup and drawdown, it has almost run its course. According to the 2025 Trustees’ report, Social Security’s OASI trust fund will be depleted in 2033. If the OASI trust fund were authorized to borrow from its sister Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund, which is better funded but much smaller, the depletion date for the combined OASDI trust funds would be pushed out by one year, to 2034.

What happens when the trust fund is empty? Since program expenditures by law cannot exceed earmarked tax revenue once the trust fund is depleted, benefits would have to be reduced. Most experts assume that the benefit reduction would need to be across the board, since there are no rules in place for prioritizing some types of beneficiaries over others. According to the 2025 Trustees’ report, an across-the-board reduction would translate into an immediate 23 percent cut in every OASI benefit check. The size of the benefit cut, moreover, would grow each year along with the growth in the size of the program’s cash deficit.

A Moving Target

The official measure of Social Security’s financial status, long used by the Trustees, is its 75-year actuarial balance. This balance, leaving aside some trivial details, is equal to the present value of earmarked tax revenue over the next seventy-five years plus the current trust-fund balance, minus the present value of projected program expenditures over the next seventy-five years and a target trust-fund reserve sufficient to finance one year of benefits at the end of the valuation period. As of 2025, OASI’s actuarial balance was a deficit of $27 trillion, or 3.95 percent of the present value of taxable payroll over the next seventy-five years. Including the DI program, OASDI’s combined actuarial deficit was 3.82 percent of taxable payroll.

Proposed reforms to Social Security are almost always evaluated in terms of their impact, plus or minus, on its 75-year actuarial balance. A reform package that closes the program’s actuarial deficit, thus restoring it to “close actuarial balance,” would be deemed to have eliminated its funding shortfall.

Given its importance in evaluating reforms, it is worth noting some peculiarities and limitations of the 75-year actuarial balance measure. To begin with, it is a moving target. All other things being equal, Social Security’s actuarial balance will deteriorate each year as relatively low-cost years (in today’s younger America) are dropped from the 75-year valuation period and relatively high-cost years (in tomorrow’s older America) are added to it. This means that a reform package that closes Social Security’s actuarial deficit over the next seventy-five years may not have closed it over the next seventy-six years.

The 75-year actuarial balance measure also implicitly assumes that near-term surpluses can be used to finance long-term deficits. From a programmatic perspective, the conventions of trust-fund accounting mean that they can be. From a fiscal or economic perspective, it is less clear that they alleviate the burden of financing the program, since trust-fund IOUs can only be redeemed if future Congresses hike taxes, cut other spending, or borrow more from the public.

The nature of trust-fund assets aside, there is another caveat about 75-year actuarial balance to keep in mind. A reform package could well return Social Security to close actuarial balance, thus “solving” its long-term financing problem, yet leave it running large cash deficits at the end of the valuation period. In this case, the solution would still leave the program facing deep benefit cuts when the trust fund is depleted.

Finally, like any measure of Social Security’s financial status, the calculation of its 75-year actuarial balance depends on a host of demographic, economic, and programmatic projection assumptions. To better capture the range of possible outcomes, the Trustees calculate three projection scenarios—a low-cost, a high-cost, and an intermediate scenario. While almost all attention focuses on Social Security’s actuarial balance under the intermediate scenario, which serves as the official measure of the program’s financial status, the results of the other scenarios are worth considering.

Under the Trustees’ low-cost assumptions, OASI’s 75-year actuarial deficit is just 0.94 percent of taxable payroll, one-quarter of what it is under their intermediate assumptions, while under the Trustees’ high-cost assumptions it is 8.11 percent of taxable payroll, twice what it is under their intermediate assumptions. In a future Vantage Point, we may explain why we believe that the Trustees’ intermediate scenario is more likely to understate than overstate the size of the problem. Here we wish to make a different point. Despite the enormous range in actuarial deficits across the three scenarios, the OASI trust fund faces near-term depletion in all of them. In the high-cost scenario, it is depleted in 2031, two years sooner than in the intermediate scenario, while in the low-cost scenario it is depleted in 2036, three years later.

No Mystery

Whatever the exact size of Social Security’s funding shortfall, there is no mystery about the types of reforms that are needed to put the program on a more sustainable trajectory. Over the years, numerous commissions and policy institutes have proposed comprehensive reform plans. Most of these plans include some combination of tax hikes and benefit cuts. And most are phased in over time, shielding current beneficiaries from most sacrifice while giving current workers time to adjust and prepare.

On the tax side, common proposals include raising the cap on earnings subject to FICA taxes, subjecting unearned income to FICA taxes, and increasing the FICA tax rate itself. On the spending side, common proposals include adjusting the “bend points” in Social Security’s initial benefit formula, trimming COLAs for benefits already in current payment status, and raising Social Security’s normal retirement age and/or indexing it to life expectancy.

All of these proposals have pros and cons. All involve trade-offs. And all take away something from someone, which is why Congress, year after year, ignores the Trustees’ warnings.

Continued inaction can only result in one of two outcomes. The first, which we have already discussed, would be tragic: deep and sudden benefit cuts that could impose severe hardship on beneficiaries.

The second outcome would be farcical. While trust-fund accounting is supposed to foster fiscal discipline, it can be gamed. Nothing would prevent Congress from earmarking some unrelated revenue source, such as the corporate income tax, to the OASI trust fund, thus rendering it solvent with the stroke of a pen. This would of course do nothing to change the federal government’s revenues, expenditures, or borrowing balance with the public, and would therefore do nothing to make Social Security more affordable. But it would allow scheduled benefits to be paid, at least for a while.

Given the state of our political economy, it is difficult to be optimistic. Still, there is room to hope that, in the end, Congress will act responsibly, if only out of enlightened self-interest. Social Security, after all, is America’s most important social program. Including DI, it currently has 68 million beneficiaries, many of whom depend on it for most of their income and many of whom vote. A Social Security trainwreck would not just ruin lives, but political careers.