The Key Role of Downside Risk in VBC’s Success

VBC Mini Briefs from Terry Health

January 9, 2024

The basic idea behind value-based care (VBC) is simple. By encouraging providers to focus on the value rather than the volume of the services they deliver, it will be possible to bend the healthcare cost curve while at the same time improving clinical outcomes. With the United States now spending at least 50 percent more per capita on healthcare than any other developed country, yet lagging every other developed country in life expectancy, achieving these twin goals could hardly be more important.

Unfortunately, VBC’s success is far from guaranteed. Indeed, a recent Terry Health survey of providers, payers, and hybrid “pay-viders” suggests that it will have to overcome many obstacles. Chief among these is the reluctance of providers to assume downside risk, the essential ingredient without which VBC lacks sufficiently strong incentives to change provider behavior and achieve its twin goals.

The full report on Terry Health’s survey, 2023 Perspectives on Value-Based Care, was published in September 2023. In this mini brief, we focus on the key role of downside risk in VBC’s success.

The Greatest Obstacle

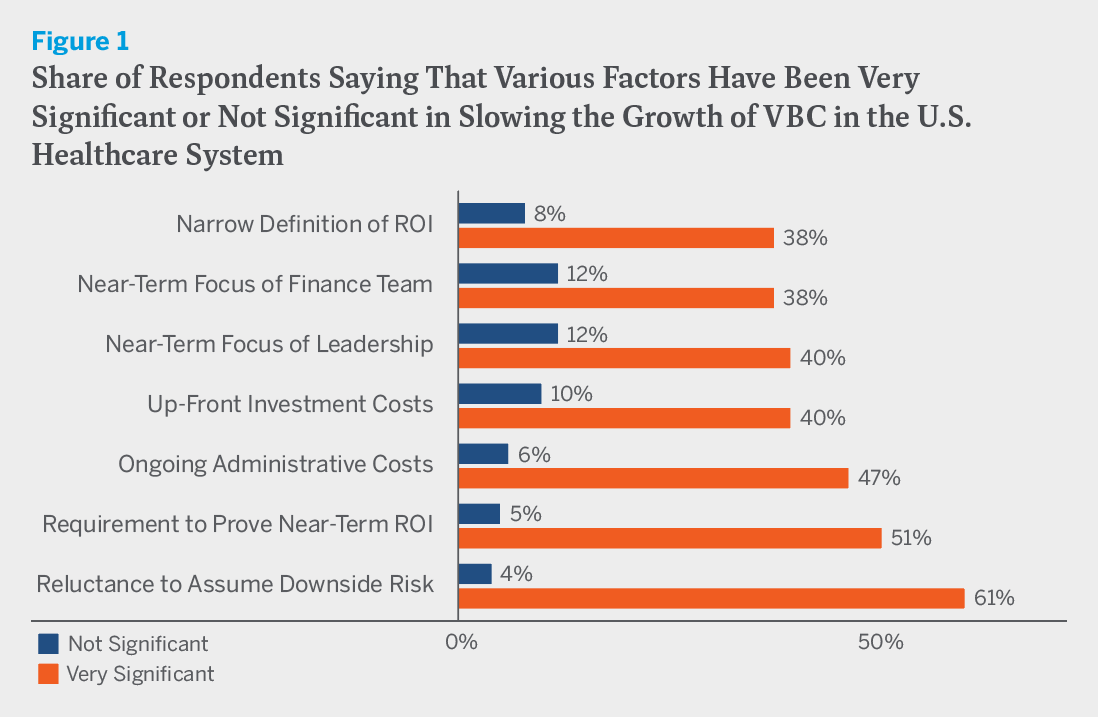

We asked survey respondents how significant various factors have been in slowing the growth of VBC in the U.S. healthcare system. To judge by their responses, there are many obstacles to VBC’s expansion. There is the need of healthcare organizations to prove near-term ROI, which half of respondents thought was a very significant factor in slowing VBC’s growth, as well as the narrow and purely financial definition of ROI, which two-fifths of respondents thought was a very significant factor. Substantial shares of respondents also cited the near-term focus of leadership and the finance team, which is no doubt related to concerns about ROI, as well as up-front investment costs and ongoing administrative costs.

According to respondents, however, the greatest obstacle is reluctance to assume downside risk. Three in five (61 percent) said that it is a very significant factor in slowing VBC’s growth, while just one in twenty-five (4 percent) said that it is not at all significant. (See figure 1.) Not surprisingly, the level of concern about downside risk varies by organization size. While 75 percent of respondents at small organizations cited it as a very significant factor in slowing VBC’s growth, just 55 percent of those at very large ones did. The level of concern, however, does not vary by organization type. Providers, payers, and hybrids were all equally likely to say that reluctance to assume downside risk is a very significant factor in slowing VBC’s growth.

Actually, it’s even worse than that. The reluctance to assume downside risk not only threatens to slow the growth of VBC, but also threatens to neuter it. Shifting from volume to value will require sweeping changes in provider practice patterns that have evolved in response to today’s dominant fee-for-service (FFS) payment paradigm. Yet much of what now passes for VBC involves little more than pay-for-performance bonuses and upside-only shared savings arrangements. It is doubtful that these provisions create incentives powerful enough to fundamentally alter provider behavior. Payment arrangements that involve significant downside risk, and especially full capitation, might. But these remain the exception rather than the rule.

This is borne out by the payment arrangements in respondents’ own VBC programs. While 89 percent of providers from organizations with commercial VBC contracts report that their contracts include pay-for-performance, just 53 percent report that they include shared savings with downside risk and just 33 percent report that they include comprehensive population-based payment. The numbers for Medicare and Medicaid contracts are similar.*

Serious Capability Gaps

What accounts for the reluctance of providers to assume downside risk? Part of the explanation no doubt lies in the prevailing medical culture. Physicians are trained to do whatever they possibly can for their patients, not to weigh cost-benefit tradeoffs when making treatment decisions. Yet weighing cost-benefit trade-offs is precisely what is required when exposed to downside risk.

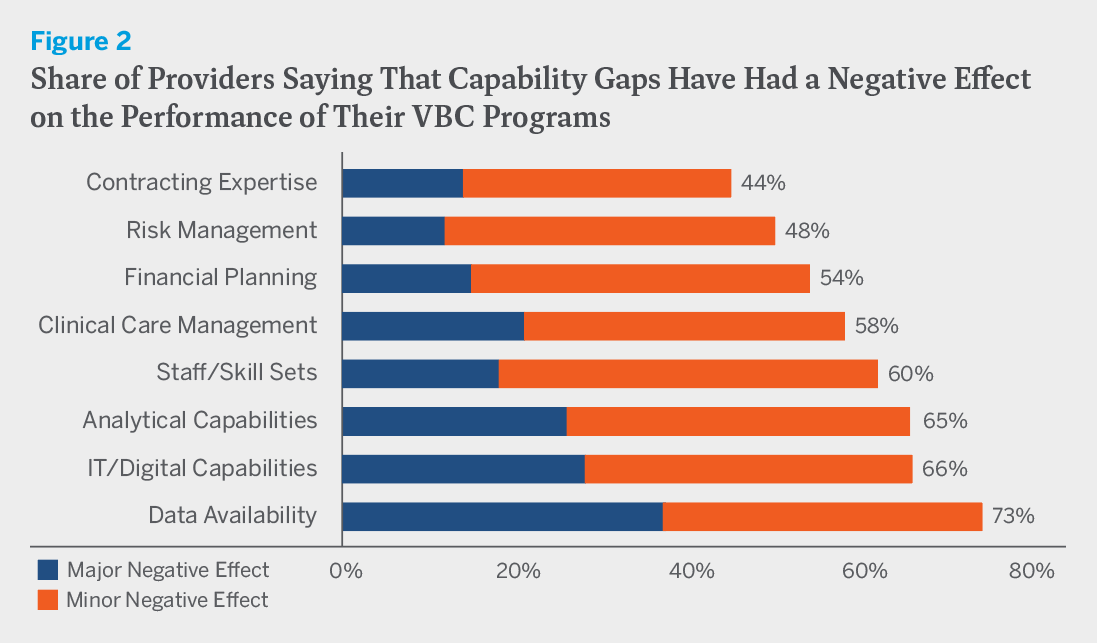

There is also a more mundane explanation. Medical culture aside, many providers simply lack the capabilities needed to succeed in two-sided risk arrangements. We asked respondents whether gaps in a variety of areas have negatively affected the performance of their VBC programs. Nearly three-quarters of providers reported that gaps in data availability have done so, while nearly two-thirds reported that gaps in analytical capabilities and IT/digital capabilities have. Smaller but still substantial shares also reported having gaps in contracting expertise, risk management, financial planning, clinical care management, and staff/skill sets. (See figure 2.)

Gaps in data availability and analytical and IT/digital capabilities in particular are serious ones to have in a VBC environment. After all, success in VBC depends on knowing and treating the whole person, not just handling an isolated episode of care. To do this effectively, providers need to follow how patients fare from one stage of their medical journey to the next, both within their own practice and outside of it. The stress on holistic care and the need for greater attention to transition management in turn mean that providers must undertake more extensive tracking, perform more extensive analysis, and produce more extensive documentation than would normally be the case in an FFS environment.

To be sure, these capability gaps do not necessarily preclude providers from participating in VBC. If their contracts simply provide for pay-for-performance bonuses and upside-only shared savings arrangements, the worst that can happen is that they will fail to reap additional financial rewards. But if providers are considering contracts that involve downside risk, these gaps can be a show-stopper.

A Tipping Point

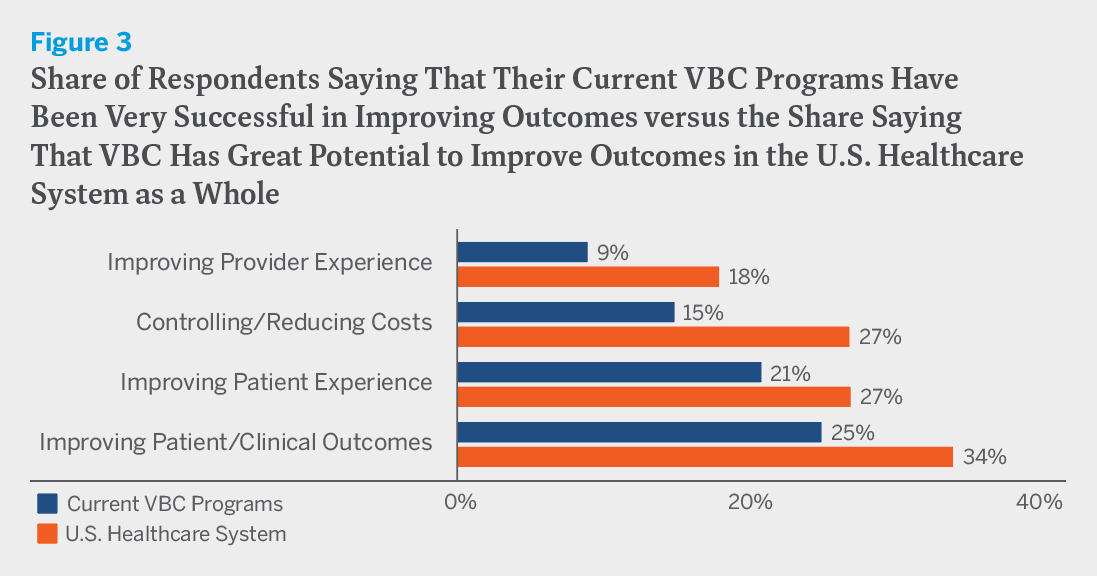

When it comes to VBC’s future, there is some good news and some bad news. The bad news is that VBC is currently having only a marginal impact on how the healthcare system works. Only small minorities of respondents to Terry Health’s 2023 survey believe that their own VBC programs have been very successful in advancing the quadruple aim of improving patient/clinical outcomes, controlling/reducing costs, and improving patient and provider experience, and only slightly larger minorities believe that VBC will be very successful in advancing the quadruple aim in the U.S. healthcare system as a whole. (See figure 3.) The good news is that all of this could change if, rather than the exception, the inclusion of downside risk in VBC became the rule.

The place to start is to close the capability gaps that discourage providers from assuming downside risk or else undermine the performance of their VBC programs when they do assume it. On the data front, this will mean ensuring IT system interoperability among providers and between providers and payers. At the same time, providers will need to upgrade their IT/digital and analytical capabilities, either by staffing up or by enlisting the assistance of outside consultants. None of this will be easy or costless, but if done right it will yield significant positive returns over time.

Addressing the other obstacles to VBC’s growth that survey respondents have identified would also be helpful. The improvements in patient health that VBC can yield, as well as the associated cost savings, may take several years to materialize. Yet standard measures of ROI are calculated over a one-year plan horizon, and also fail to take into account important indirect benefits, such as those attributable to improved staff productivity and enhanced brand appeal. A longer-term and more expansive measure of ROI is clearly needed. If ROI were appropriately measured, moreover, it might turn out that the upfront VBC investment costs which now seem to hurt the bottom line actually help it, while ongoing administrative costs would surely appear more affordable. Leadership and the finance team would also be more likely to shift their focus from the near term to the long term.

The prevailing medical culture will be more difficult to change. But this too will happen if downside risk becomes an increasingly common feature of VBC contracts. As things stand, providers often default to FFS practice patterns, regardless of contract type. In time, a tipping point may be reached when the default flips to VBC practice patterns. This, at least, is what we should all hope.