Why Providers Are Struggling to Succeed in Value-Based Care

VBC Mini Briefs from Terry Health

November 9, 2023

As the U.S. healthcare industry moves further into value-based care (VBC), providers are being compelled to reformulate their operations, business models, and risk arrangements. CMS, which is helping to drive the shift, hopes that encouraging them to focus on the value rather than the volume of the services they deliver will both bend the cost curve and improve clinical outcomes.

An obvious question that is often overlooked in the rush to promote VBC is whether providers are equipped to navigate the transformation. Terry Health’s 2023 VBC survey of providers, payers, and hybrid “pay-viders” suggests that there are reasons for concern. Many providers report that capability gaps are having a negative effect on the performance of their VBC programs. Many, moreover, are unhappy with the terms and conditions of their VBC contracts, which they perceive as favoring payers. There are also more fundamental obstacles to providers’ success, including the fragmentation of the healthcare financing system, which ends up blunting VBC’s cost-saving incentives, and a medical culture that has trouble acknowledging the need for cost-benefit tradeoffs.

The full report on Terry Health’s VBC survey, 2023 Perspectives on Value-Based Care, was published in September 2023. In this mini brief, we take a closer look at the issue of provider preparedness.

Reasons for Concern

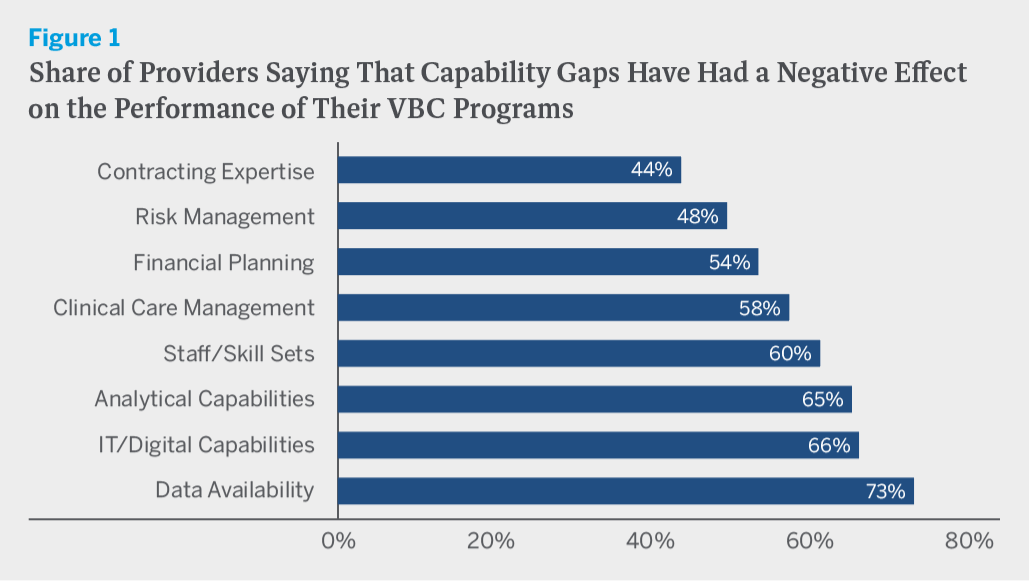

Let’s start with capability gaps. We asked survey respondents whether capability gaps in a variety of areas have negatively affected the clinical and/or financial performance of their VBC programs. Data availability was the most frequently cited gap, with three-quarters of providers reporting that a gap there has had either a major or a minor negative effect on performance. Data gaps might arise because the clinical data that providers need to make informed treatment decisions are incomplete or unavailable due to HIPAA privacy restrictions or a lack of IT system interoperability with other providers. Gaps might also arise because payers neglect to share relevant claims data with providers, or perhaps cannot share the data because of interoperability issues. Whatever the reasons, it is hard to imagine a more serious problem. Data, after all, are VBC’s lifeblood.

Two-thirds of providers also report having gaps in analytical capabilities and IT/digital capabilities, while smaller but still substantial shares report having gaps in contracting expertise, risk management, financial planning, clinical care management, and staff/skill sets. (See figure 1.) You might think that the smallest provider organizations would be much more likely to report having capability gaps than the largest ones. But with the exception of contracting expertise, this is not the case. Capability gaps negatively affect VBC performance at provider organizations of all sizes.

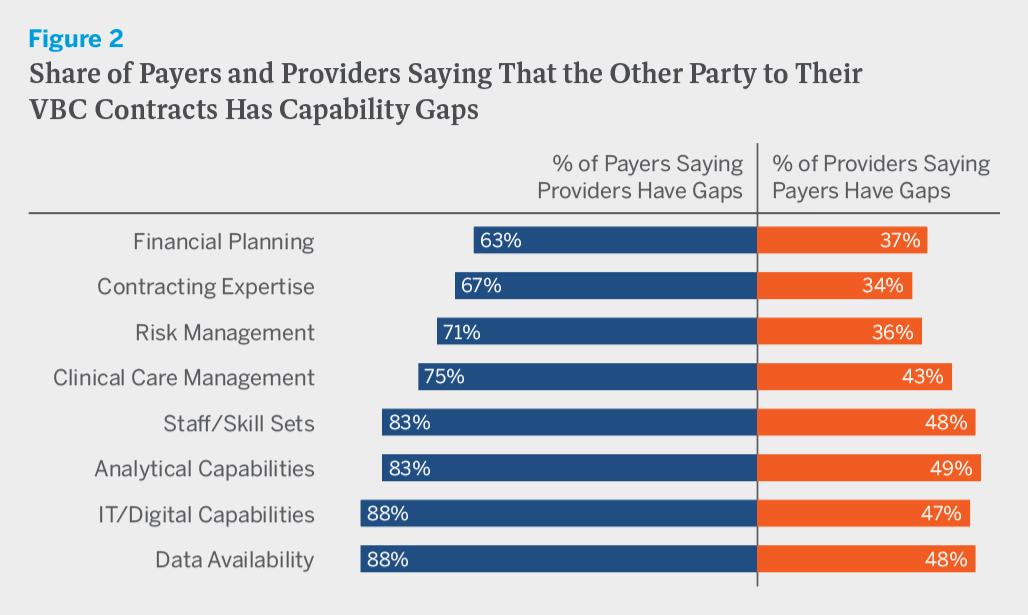

In addition to asking respondents about capability gaps in their own organizations, we also asked them whether they think that capability gaps in the counterpart organizations with which they have VBC contracts have negatively affected the performance of those organizations. In every area, payers were much more likely to say that their provider counterparts have capability gaps than providers were to say that their payer counterparts do. In other words, providers seem to believe that payers are prepared to succeed in a VBC world, while payers doubt that providers are. (See figure 2.)

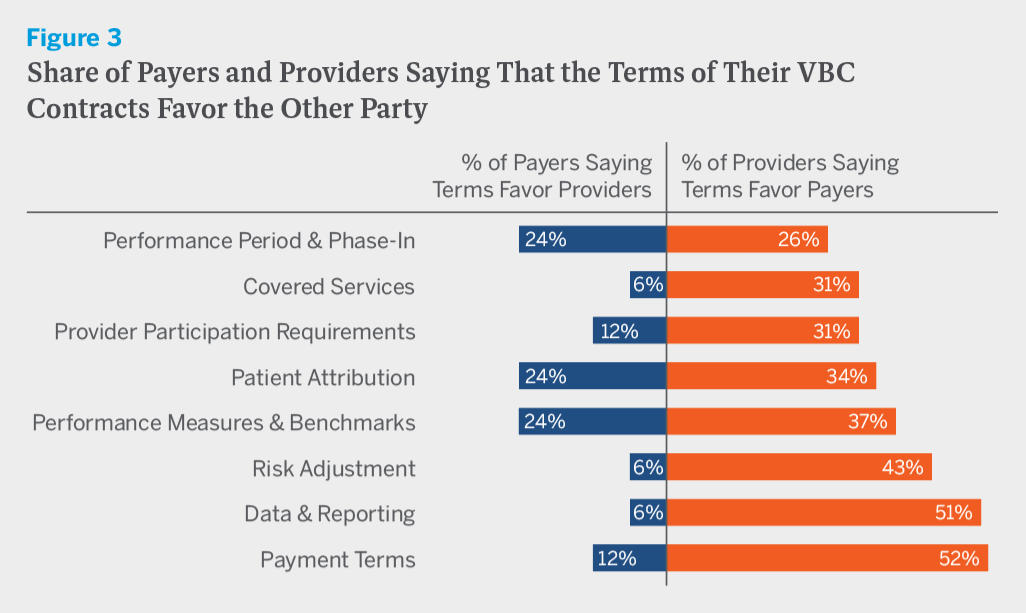

Now let’s turn to VBC contracts. We asked survey respondents whether the terms and conditions of their contracts favor their own organization, the other party to the contract, or are neutral in the sense that they are fair and equally benefit both parties. In every contract area, from covered services to payment terms, providers were more likely than payers to believe that contracts favor the other party, and in some areas, including covered services, risk adjustment, data and reporting responsibilities, and payment terms, they were far more likely to believe this. (See figure 3.)

Given the inherent imbalance in bargaining power between most payers and most providers, it seems entirely plausible that the terms of VBC contracts would, more often than not, favor payers. But even if they don’t, there is still a problem. The mere fact that providers perceive the terms as unfair threatens to dampen their enthusiasm for VBC and undermine its long-term growth.

Leaving aside the survey findings for a moment, it’s worth considering some more fundamental obstacles to providers’ VBC success. The place to begin is with the fragmentation of the healthcare financing system. Whether payers are dealing with fee-for-service (FFS) contracts or VBC contracts, their financial goal is always the same: to reduce costs. For providers, the goal depends on the type of contract. If it is a VBC contract, their financial goal is to reduce costs. But if it is a FFS contract, their financial goal is to increase revenues. The problem is that most providers have both types of contracts. Since, legally and ethically, providers cannot treat patients differently based on their health plan, many end up defaulting to FFS practice patterns, regardless of the contract type. This dynamic, which blunts VBC’s cost-saving incentives, will be difficult to change so long as FFS remains the dominant financing arrangement.

The tendency of providers to default to FFS practice patterns is naturally reinforced by the prevailing medical culture. Physicians are trained to do whatever they possibly can for their patients, not to weigh cost-benefit tradeoffs. It is doubtful that the kinds of pay-for-performance and shared savings provisions on which most VBC contracts currently rely create incentives that are powerful enough to fundamentally alter medical culture and provider behavior. Provisions that subject providers to significant downside risk, and especially full capitation, might well succeed in doing so. But for now, such provisions remain the exception rather than the rule.

Finally, there is the matter of provider experience. The past half century in healthcare has witnessed the rise of corporate medicine, the erosion of physicians’ professional autonomy, and a massive increase in administrative burdens that crowds out time spent on patient care. Not coincidentally, the past half century has also witnessed a dramatic decline in physician job satisfaction, a dramatic increase in physician burnout, and a wave of early retirements.

VBC doesn’t improve any of this, and in fact, by further increasing provider workload, may make it worse. To be sure, improving provider experience is not VBC’s purpose. But just as providers’ perceptions about the fairness of VBC contracts will help to determine whether they embrace the movement or push back against it, so too will their perceptions about the VBC experience.

A Troubling Disconnect

All of this helps to explain a troubling disconnect between VBC intentions and results. Slightly over half of providers in Terry Health’s VBC survey report that a desire to promote health equity was a very important consideration in becoming involved in VBC, three-quarters report that a belief in patient-centric care was, and nearly four-fifths report that improving clinical outcomes was. Yet just 25 percent of providers believe that their VBC programs have been very successful at improving clinical outcomes and just 21 percent believe that they have been very successful at improving patient experience.

If VBC were working well for patients, it might be less concerning that it is not working well for providers. But alas, this does not appear to be the case. On reflection, moreover, it is hard to see how it could be the case. Providers are the lynchpin on which the whole healthcare system turns. For VBC to work well for patients, it will also need to work well for providers, and that will require bridging capability gaps, revisiting contract terms and conditions, and finding creative ways to surmount the more fundamental obstacles to providers’ success that are embedded in how the healthcare system works. If providers continue to struggle to succeed in VBC, it will have only a marginal impact on costs and outcomes, not the transformative one that its architects and advocates hope it will.