America’s Deepening Baby Bust

Vantage Point: Mini Briefs from The Terry Group and the Global Aging Institute

May 15, 2024

The U.S. fertility rate fell to an all-time historical low of 1.62 in 2023, dashing hopes that a brief post-pandemic uptick in birthrates might herald the end of America’s baby bust. Now it looks more and more like low fertility is here to stay.

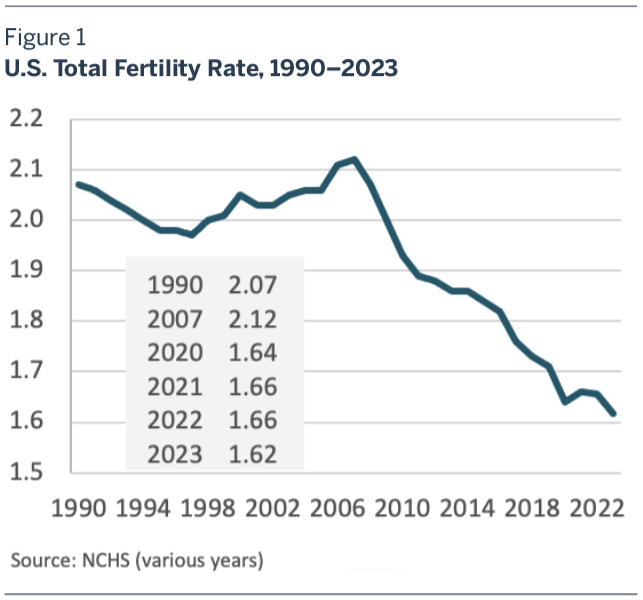

According to the CDC, the U.S. total fertility rate (TFR), a measure of average lifetime births per woman, resumed its decline in 2023, falling to an all-time historical low of 1.62. The drop more than erased a post-pandemic uptick in the TFR that some experts hoped might herald the end of America’s baby bust. Now it looks more and more like low fertility is here to stay.

In this Vantage Point, we review the latest fertility numbers and explain why a rebound in U.S. birthrates seems increasingly unlikely.

Almost Continuous Decline

For nearly two decades prior to the Great Recession, the U.S. TFR hovered between 2.0 and 2.1, close to the so-called replacement rate needed to maintain a stable population from one generation to the next. Since then it has been in almost continuous decline, tumbling from 2.12 in 2007 on the eve of the Great Recession to 1.64 in 2020 in the midst of the pandemic lockdowns. The TFR then briefly reversed direction, rising to 1.66 in 2021 and holding steady at that level in 2022. In 2023, however, it resumed its decline, dropping to 1.62, an all-time historical low and nearly one-quarter less than its level in 2007. (See figure 1.)

For a while, the post-pandemic uptick in the TFR gave rise to hopes that America’s baby bust might finally be ending. At the time we argued that, rather than a turnaround, the uptick was likely a one-time bounce caused by women who had postponed planned births during the pandemic rushing to recoup them. (See “Is America’s Baby Bust Over?”) The new CDC data for 2023, released in April, would seem to vindicate our assessment.1

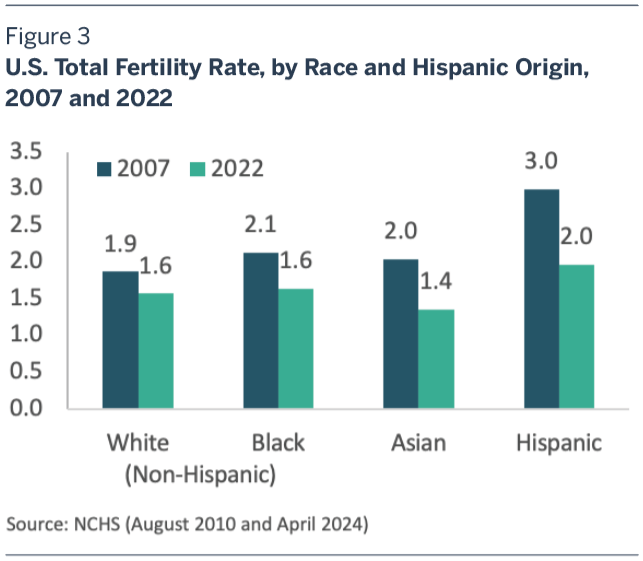

Indeed, there is not even the slightest hint in the new data that a turnaround is imminent, much less under way. From 2022 to 2023, the U.S. TFR declined by 2.4 percent, more than its 1.7 percent average annual rate of decline since 2007. Moreover, birthrates fell among women of every race and ethnicity. Perhaps most tellingly, they also fell among women in their thirties as well as among women in their twenties.

What Tempo Effect?

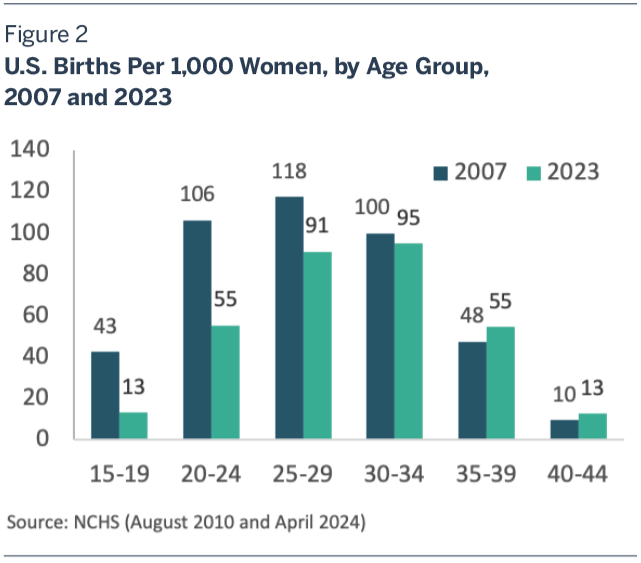

The latest age bracket data on fertility throw yet more cold water on the notion that America’s baby bust is merely the artifact of a “tempo effect.” When the U.S. TFR first started to decline in the wake of the Great Recession, many demographers assumed that young women were simply postponing family formation until later in life, rather than deciding to have fewer children, and that birthrates would eventually rise at older ages, pushing the TFR back up.

Tempo effects can be real. As the Baby Boom generation came of age starting in the late 1960s, the U.S. TFR plunged, bottoming out at 1.74 in 1976. But by the 1990s, as late-birthing Boomers began to have children in large numbers, it had recovered to the 2.0 to 2.1 range. Fast forward to the 2010s, and it seemed reasonable to assume that Millennials, like Boomers before them, were just pushing out childbearing until later in life.

Alas, this does not appear to be the case. Sixteen years have already passed since America’s baby bust began, and the oldest Millennials are now reaching the end of their childbearing years. Yet far from being higher than it was in 2007, the birthrate of women in their early thirties, the age when one would expect a tempo effect to kick in, is actually lower. And though the birthrates of women in their late thirties and early forties have risen slightly, the increases are far too small to make up for the enormous decline in birthrates among women in their twenties. (See figure 2.)

A More Normal Developed Country

It is tempting to think that America’s baby bust is an aberration, and that the TFR will necessarily climb back to its higher pre-Great Recession level. But in fact it was the higher level that was the aberration. Between 1990 and 2010, the U.S. TFR exceeded that of every other developed country except Iceland, Israel, and New Zealand. Today, it is about equal to the OECD average. When it comes to fertility behavior, America has simply become a more normal developed country.

We are skeptical that this will change anytime soon. The decline in the U.S. TFR has been broad-based, encompassing Americans of all races and ethnicities. (See figure 3.) Moreover, none of the social and economic trends that have helped to depress birthrates show signs of reversing. The age of first childbirth continues to rise. Religiosity, which is highly correlated with fertility, continues to decline. And it remains much more difficult for Millennials and Zoomers to launch careers and establish independent households than it was for Boomers and Xers at the same age.

To be sure, demographers have sometimes been surprised by unexpected shifts in fertility behavior. Few if any predicted the postwar Baby Boom, and few if any predicted its end. In truth, no one knows what the U.S. TFR will be five years from now, much less fifty. But absent a crystal ball, it seems prudent to assume that fertility will remain low for the foreseeable future.

The CBO, whose latest projections assume that the U.S. TFR will average 1.7 over the rest of the century, clearly agrees. So does the UN Population Division, which also assumes that it will average 1.7, and the U.S. Census Bureau, which assumes that it will average 1.6. Among major projection-making agencies, only the Social Security Administration’s Office of the Actuary still seems to be hoping that a much delayed tempo effect will finally lift the TFR. Yet in its 2024 Trustees Report, released earlier this month, even it has lowered its ultimate fertility assumption from 2.0 to 1.9.

America’s deepening baby bust has profound implications for its future. Lower fertility means that the population will age more and that fiscal burdens will rise higher than would otherwise have been the case. Over time, lower fertility also means that the workforce, and hence GDP, will grow more slowly. Since national power depends critically on fiscal and economic capacity, it may even mean that America’s geopolitical stature will diminish.

Given the stakes, one might hope that policymakers would be focused on finding ways to stem the U.S. fertility decline. There is, after all, a persistent gap between how many children American women say that they want and how many they are actually having, and the right social and economic policies might help to narrow it. But here too, as with so many other challenges, our political economy appears incapable of taking constructive action.