America’s Rapidly Deteriorating Demographic Outlook

Vantage Point: Mini Briefs from The Terry Group and the Global Aging Institute

November 30, 2023

According to new Census Bureau projections, the U.S. population will peak later in the century, then decline. Until just a few years ago, it seemed certain that the United States would have a growing population for the foreseeable future. What explains the rapid deterioration in America’s demographic outlook? And what does it mean for the budget, the economy, and America’s place in the world?

According to new Census Bureau projections released in November, the U.S. population, which was 333 million in 2022, will peak at 369 million in 2080, then gradually decline.1 These projections, moreover, assume that net immigration will average nearly one million a year. Without immigration, America’s population would peak next year, then enter a much steeper decline. By the end of the century, it would be one-third smaller than it is today.

Until just a few years ago, it seemed certain that the United States, unlike most of its developed world peers, would have a growing population for the foreseeable future. What explains the rapid deterioration in America’s demographic outlook? And what does it mean for America’s future? In this Vantage Point, we discuss the new Census Bureau projections and consider their long-term fiscal, economic, and geopolitical implications.

The Collapse in U.S. Birthrates

The change in America’s demographic fortunes has been both large and swift. As recently as 2017, when the Census Bureau last revised its long-term population projections, it expected that the U.S. population would grow to 404 million by 2060, its projection horizon at the time. In its current projections, it expects that the U.S. population will be just 364 million in 2060. That’s 40 million fewer people, a number roughly equal to the population of Canada.

Most of the population shortfall is explained by the collapse in U.S. birthrates, which the previous Census Bureau projections did not fully reflect, but which the new ones do.

Until the Great Recession, the United States was a demographic outlier among developed countries. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, its total fertility rate (TFR), a measure of average lifetime births per woman, hovered between 2.0 and 2.1, far above the OECD average and close to the replacement level needed to maintain a stable population from one generation to the next. Together with substantial net immigration, America’s unusually high fertility rate seemed to ensure that it would still have a growing population and a growing workforce, even as those in other developed countries stagnated or contracted.

No longer. The U.S. TFR began to decline in 2008, and it has continued to decline almost every year since. As of 2022, it stood at 1.67, slightly above its all-time low of 1.64 registered in 2020 in the midst of the pandemic, but still far beneath its 2.12 level in 2007, the year before the slide in U.S. birthrates began.

Initially, most demographers assumed that the decline in the U.S. TFR was a mere “tempo effect” that would soon be reversed. Millennials, the thinking went, were postponing family formation until later in life, rather than having fewer children. As they grew older and recouped the births they had deferred, the TFR would eventually recover. But that is not what has happened. Over the past fifteen years, birthrates have remained more or less flat among women in their thirties, even as they have continued to fall among women in their twenties. (See figure 1.) Rather than being the result of a tempo effect, it seems increasingly clear that the decline in the U.S. TFR reflects a more lasting shift toward smaller family size.

The Census Bureau certainly thinks so. Indeed, its new projections assume that, rather than rise, the U.S. TFR will continue to fall. More precisely, they assume that the fertility rate of native-born white women will remain unchanged at its current level and that the fertility rates of women of other races and ethnicities, both native born and foreign born, will ultimately converge with it. This dynamic is expected to gradually pull down the TFR to 1.52.

The Census Bureau is not alone in its belief that low fertility is here to stay. In its latest projections, the UN Population Division assumes that the U.S. TFR will average 1.70 over the rest of the century, while the CBO in its latest projections assumes that it will average 1.75. Among major projection-making agencies, only the Social Security Administration’s Office of the Actuary, which assumes that the TFR will rebound to 2.0, still seems to be hoping that a much delayed tempo effect will finally kick in.

Is it certain that U.S. birthrates will remain permanently depressed? Of course not. Demographers have been surprised before by unexpected shifts in fertility behavior. Few if any predicted the start of the postwar baby boom in the mid-1940s, and few if any predicted its end in the mid-1960s. But absent a crystal ball, we believe that the prudent projection choice is to assume a continuation of low fertility.

To better understand why, it helps to consider how much has changed in recent decades. Americans are much less optimistic about the living standard prospects of their children, not to mention the country’s overall direction, than they were a generation ago. They are also much less religious, and degree of religious conviction is highly correlated with fertility across all of the world’s major monotheisms. Perhaps most importantly, it has become much more difficult for Millennials and Gen-Zers to establish independent households and launch careers than it was for Boomers or Gen-Xers at the same age.

When it comes to fertility behavior, America used to be exceptional. But as these shifts have unfolded, it has become a more normal developed country in which delayed marriage, delayed childbearing, and smaller family size are the norm. Although the Census Bureau’s fertility assumptions may seem pessimistic, a TFR of around 1.5 would not place the United States anywhere near the low end of the developed world spectrum. In fact, it would place it close to the current average for high-income OECD countries.

The Decisive Role of Immigration

The collapse in U.S. birthrates means that, one way or the other, immigration will play a decisive role in determining America’s demographic direction. Since the future level of immigration is potentially subject to much more variation than future fertility rates are likely to be, the range of possible outcomes is wide indeed.

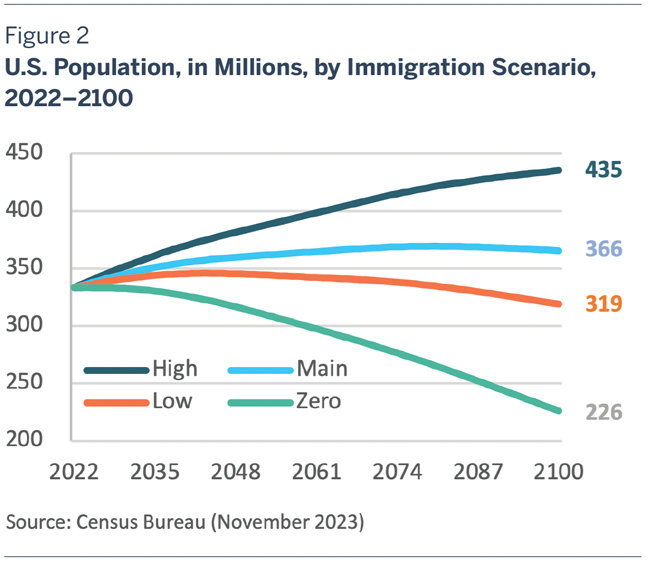

The Census Bureau publishes several population projection scenarios, all of which share the same fertility and mortality assumptions but which differ in the level of net immigration they assume. In the Census Bureau’s “main series,” which serves as its official projection, net immigration is assumed to average 0.9 million per year, about what it has since the Great Recession. With this level of immigration, the U.S. population is projected to peak at 369 million in 2080, then decline gradually to 366 million by 2100. In the Census Bureau’s high immigration scenario, which assumes that net immigration will average 1.5 million per year, the U.S. population would continue growing throughout the century, reaching 435 million by 2100, while in its low immigration scenario, which assumes that net immigration will average 0.5 million per year, the U.S. population would peak at 346 million in 2043, then decline to 319 million by 2100.

The Census Bureau also publishes an illustrative zero immigration scenario which, as its name suggests, assumes that there will be no net immigration in the future. In this scenario, the U.S. population would peak next year, then decline precipitously to 226 million by 2100, a drop of one-third. (See figure 2.)

The future level of immigration will not only affect the size of America’s population, but also its age structure. Since immigrants on average tend to be younger than the native-born population, less immigration means that America will age more while more immigration means that it will age less. Although the impact of immigration on age structure is not as dramatic as its impact on population growth, it is still significant. By 2100, the share of America’s population that is aged 65 and over would range from a low of 27 percent in the high immigration scenario to a high of 36 percent in the zero immigration scenario. (See figure 3.)

Some Serious Challenges

There would no doubt be some benefits to having a stagnant or contracting population. From a quality of life perspective, for instance, it may mean less urban congestion, while from an environmental perspective it may mean a smaller carbon footprint. But at the same time, having a stagnant or contracting population would also pose some serious challenges. We discussed these challenges in depth in an earlier issue brief (“Why the Collapse in U.S. Population Growth Matters,” April 21, 2022). Here we limit ourselves to a brief overview.

To begin with, there is the fiscal challenge. Graying means paying—more for pensions, more for health care, and more for long-term care for the elderly. An America with a stagnant or contracting population will also be an America with a faster-aging population. And the more America ages, the larger the fiscal burden of old-age benefit spending will grow and the more painful the necessary fiscal adjustments will become.

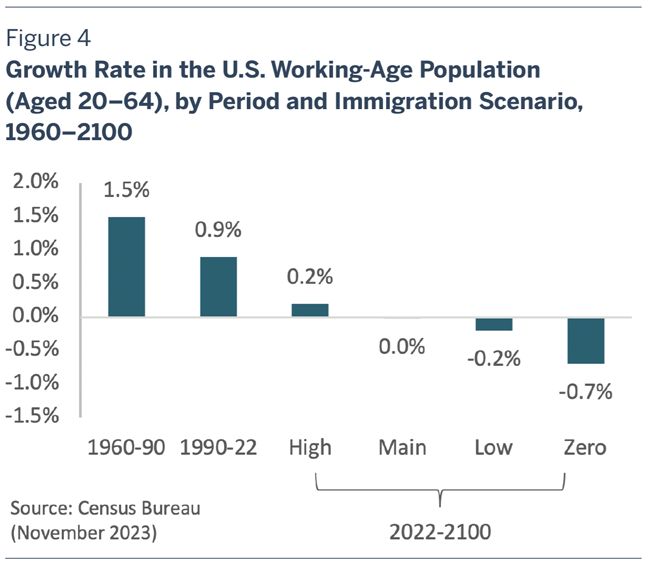

Then there is the economic growth challenge. There are two components to GDP growth: employment growth and productivity growth. All other things being equal, a more slowly growing or contracting working-age population will mean a more slowly growing or contracting workforce, and a more slowly growing or contracting workforce will mean a more slowly growing GDP. Historically, growth in the working-age population, and hence employment, has been a major driver of U.S. economic growth. Yet according to the Census Bureau’s main projection series, the U.S. working-age population will not grow at all over the rest of the century, meaning that it will add nothing to GDP growth. In its low immigration and zero immigration scenarios, the working-age population would contract, meaning that it would subtract from GDP growth, and in the zero immigration scenario it would greatly subtract from it. (See figure 4.)

As America’s demographics deteriorate, economic growth will increasingly depend on productivity growth. Yet there are reasons to believe that productivity growth will also slow in an aging America with a stagnant or contracting population. A smaller workforce will mean less demand for private investment and a slower turnover in the capital stock. At the same time, widening fiscal deficits due to growing old-age benefit spending may crowd public investment out of government budgets. An aging workforce may also be less flexible, less mobile, and less entrepreneurial.

Finally, there is the geopolitical challenge. While population size alone does not confer geopolitical stature, population size and economic size together are potent twin engines of national power. They obviously underpin the hard power of military capabilities. To some significant extent, they also underpin the soft power of global influence, which depends in part on a country’s leverage in multilaterals, its global business presence, and its dominance in the media and popular culture, all of which in turn depend in part on its size. An America that is demographically and economically stagnant or contracting may find it increasingly difficult to enforce today’s rules-based world order.

Four Important Policy Lessons

It isn’t within the Census Bureau’s purview to draw policy lessons from its population projections, but it is within ours. We believe that there are four important ones.

The first is that immigration is a vital resource for an aging America, and that curtailing it would also curtail economic growth. This does not mean that America should throw open its borders. What it does mean is that it needs to ensure that levels of legal immigration are adequate to meet its future labor-market needs. Some developed countries, notably Australia and Canada, have made immigration the lynchpin of their long-term strategy for addressing the aging challenge. Perhaps the United States should do the same.

The second is that the most effective way for America to reduce its dependence on immigration would be for it to raise its TFR. While U.S. birthrates seem unlikely to increase on their own, more family-friendly public policies might make a difference. When surveyed, American women say both that they would ideally want and that they expect to have more children than they are actually having.2 This gap suggests that policies which reduce the costs of childrearing and make it easier for young adults to balance work and family responsibilities, such as subsidized daycare and paid maternity and paternity leave, might help push birthrates back up again.

The third is that, whatever happens to immigration or birthrates, America will need to do a better job of leveraging its existing human capital. The obvious place to start is to increase labor-force participation among the elderly, who are not only America’s greatest underutilized human resource but are also the fastest-growing segment of its population.

The fourth is that America should resist protectionist pressures. Open global capital markets can allow savings in older and more slowly growing developed countries like the United States to flow to investment opportunities in younger and faster-growing emerging markets. Open global labor markets can similarly allow workers in countries where labor is abundant and capital is scarce to be matched with jobs in countries like our own where just the opposite is true. Ensuring that the world remains interconnected, moreover, would not only reduce the economic costs of population aging, but could also reduce the geopolitical risks.

Unfortunately, current trends are not encouraging. Immigration has of course surged over the past few years, but the surge has occurred amid a chaotic breakdown in border security, not as the result of any coherent plan for meeting America’s labor-market needs. With inflation, home prices, and student loan debt burdens so high, the disincentives to family formation that young people face are perhaps greater than they have ever been. Although elderly labor-force participation rose rapidly in the first two decades of the century, the trend has stalled since the pandemic. Far from embracing globalization, the United States, along with much of the rest of the world, is moving in the opposite direction.

Demography may not be destiny, but the challenges it poses are real and cannot be wished away. There is still time for America to meet them, but the time to do so is fast running out.