How Healthcare Organizations Can Take the Lead in the Nation’s Quest to Improve Health Equity

July 2022

This column ran in Healthcare Financial Management Association’s (HFMA) Cost Effectiveness of Health report on July 21, 2022. It is the first in a series of columns based on The Terry Group’s “Health Equity Strategies” initiative.

Few if any healthcare professionals would deny there is a deep need to improve health equity in our nation. But most feel the problem is beyond their ability to cure, given that the root causes of disparate health outcomes tend to lie in larger social and economic issues, from poverty to discrimination.

Rather than throw up their hands, however, they should take to heart the old proverb, “Physician, heal thyself” (or more broadly, “Healthcare provider, heal thyself”). Many of the ways our healthcare system currently works exacerbate health inequity — and this is a problem we can cure.

This effort necessarily starts with identifying those features and practices within the healthcare system that contribute to health inequity and then developing actionable strategies for remedying the problems. Healthcare finance leaders will have an essential role to play in championing and advancing these strategies, reaching out to other healthcare system stakeholders to establish partnerships where necessary.a

A focus on spheres of influence

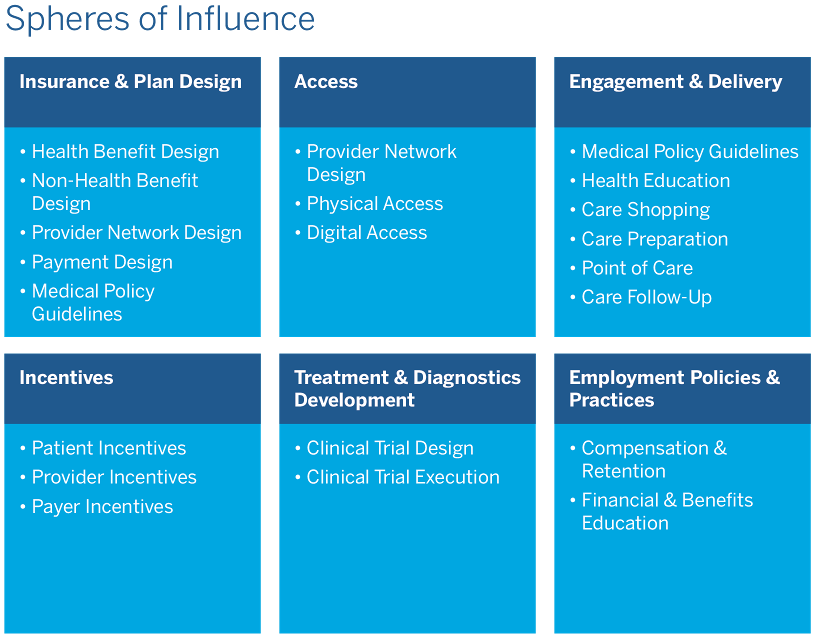

In thinking about health equity, it is useful to distinguish between spheres of concern and spheres of influence. The former involve broad social and economic issues, whereas the latter involve the workings of the healthcare system itself. There are six spheres of influence: insurance and plan design, access, engagement and delivery, incentives, treatment and diagnostics development, and employment policies and practices.

Some of the ways in which the healthcare system contributes to health inequity, such as narrow provider networks, are relatively straightforward. Others, such as reliance on historical utilization data, average clinical experience and one-year plan time horizons are more complex. But all of these problems have one thing in common: Unlike the root causes of health inequity, they can be addressed directly by healthcare system participants, including insurers, employers, providers and the benefit consultants and actuaries who advise them. Here are five critical steps that can help to improve health equity for Americans.

- Cultivate a more holistic understanding of health and healthcare. Health insurance has traditionally been limited to reimbursing the cost of medical services, without much attention to ensuring that plan members can access those services. Something as simple as including transportation to physician appointments as part of the benefits package could improve health equity. So could designing health benefits packages that better address nonmedical determinants of health, such as nutrition and lifestyle, which can have a larger impact on health than medical care.

- Promote a more personalized approach to healthcare. Practice guidelines are typically based on average clinical experience. Although this approach may be appropriate in setting insurance premiums or provider reimbursement rates, healthcare delivery should be tailored to the individual. Health equity could be improved if practice guidelines accounted not only for gender and age, but also for race and ethnicity, cultural habits and preferences and relevant socioeconomic factors.

- Focus more on long-term outcomes. A central goal of health plan design is to reduce excess utilization, which also reduces cost. Yet the one-year plan horizon typically used in assessing what is excess may fail to capture the long-term benefits of utilization and simply end up pushing health problems and health costs into future years. Similarly, the use of a one-year plan horizon for assessing ROI discourages health innovations whose benefits might not be immediately apparent but could prove to be significant over time. Although short-term plan horizons can adversely affect all members, they are likely to have a disproportionate impact on underserved populations, who already tend to underutilize services and stand to benefit most from health investments with long-term payoffs.

- Undertake a more targeted approach to cost control. Today’s blunt cost control strategies, despite being effective in some ways, often inadvertently exacerbate health inequity. The trend toward narrow provider networks may control costs in the short term, for example, but it can limit access by creating provider deserts in vulnerable communities. Similarly, the use of historical utilization data in setting provider reimbursement rates, calculating risk adjustment scores and informing predictive health models may help to control costs. But the use of this data also can exacerbate health inequity because it tends not to reflect the true health risks and needs of underserved populations.What’s needed are better targeted strategies that control costs while accounting for the needs of all populations. Reductions in the size of provider networks, for instance, could be limited so that a minimum provider-to-population ratio is maintained in all communities, while historical utilization data for at-risk populations could be supplemented by data on social determinants of health.

- Adopt more supportive employment practices. As employers, healthcare system participants can also have a direct impact on health equity. They could increase the wages and enhance the benefits they offer low-income, part-time and short-tenure employees, including health insurance, gym memberships, and mental health counseling. They could also do a better job of educating all employees about how to improve their health and well-being across their lifecycle. Approaches could include lunch and learns, employee newsletters or in-house contests to promote walking, cycling and other types of exercise.

An abundance of opportunities

There are clear opportunities to improve health equity by changing the ways our healthcare system operates. The types of approaches described here — from embracing a more holistic understanding of health and healthcare to adopting a more personalized approach with a greater focus on long-term outcomes — would be desirable and beneficial no matter what the reason might be for adopting them. They would not only allow the healthcare system to better meet the needs of underserved populations, but would also improve health outcomes for all populations.

Healthcare organizations could enjoy financial benefits from such initiatives under both value-based and fee-for-service payment arrangements. By helping to improve population health, for example, they would be in an improved position to receive incentive payments under value-based contracts. In fee-for-service settings, they could increase revenues by increasing appropriate engagement with the healthcare system.

Health equity and business success are not mutually exclusive. In fact, for hospitals and health systems, improving health equity is essential to business success. These organizations therefore should be engaged in promoting health equity not only out of a sense of social responsibility, but also because it is simply good business.

About the Authors

Richard Jackson is the president and founder, Global Aging Institute, headquartered in Alexandria, Va., and a senior advisor, The Terry Group, Chicago.

Yi-Ling Lin is head of risk analytics, The Terry Group, Chicago.

Munzoor Shaikh is executive vice president for healthcare, The Terry Group, Chicago.

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern