The Business Case for Investing in Health Equity

Health Equity Strategies No. 3

August 11, 2022

Key Learnings

- Despite the vast economic and social benefits, many promising health equity initiatives go unfunded because it is difficult to prove that they will deliver a positive ROI to the health-care organizations undertaking them. The problem is that standard ROI analysis is too focused on the near term and too narrow in scope to capture the full benefits of investing in health equity.

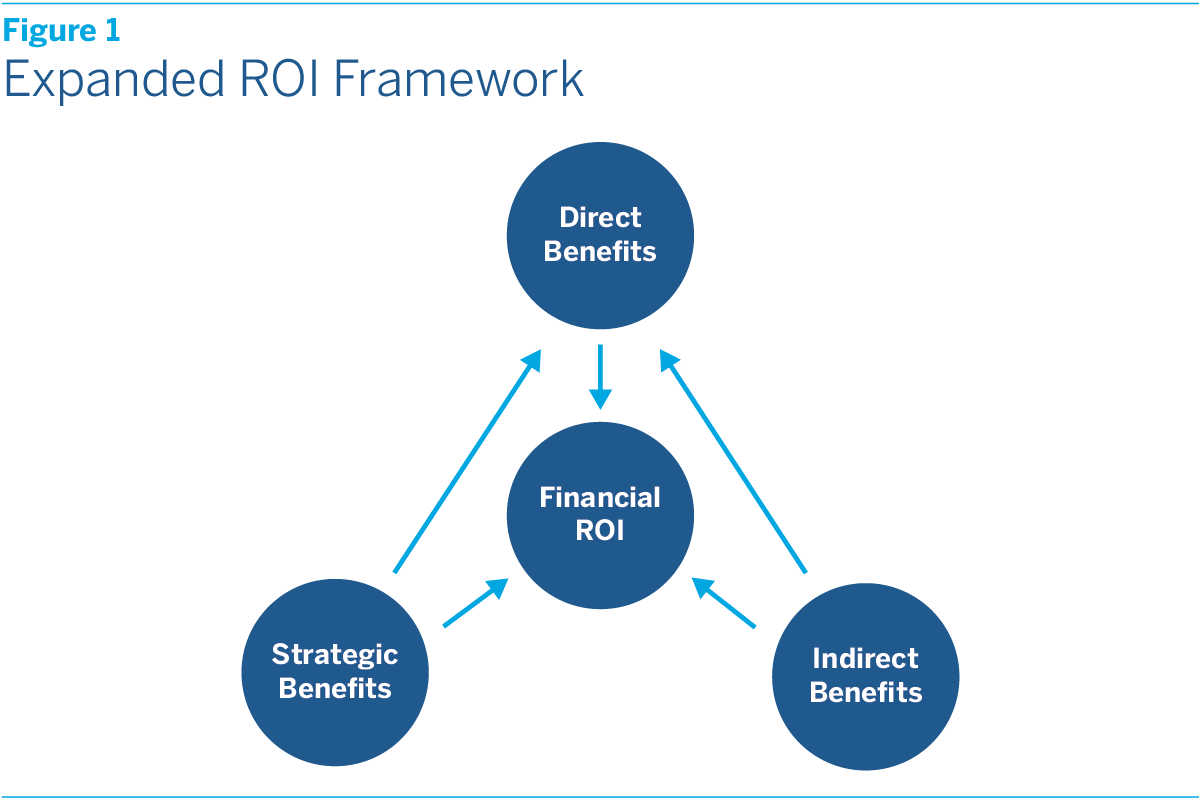

- The Terry Group proposes adopting an expanded ROI framework for evaluating health equity investments which would: (1) evaluate ROI over a longer time horizon of three to five years; (2) take into account indirect returns to health equity investments, from enhanced brand appeal to improved employee engagement and productivity; and (3) weigh the strategic advantages that can flow from promoting health equity in an America where the population is becoming more diverse, the society is becoming more aware of and committed to addressing health inequities, and the health-care system is inexorably moving toward VBC models.

- We believe that there is a compelling business case for investing in health equity. In fact, it will not only improve future business prospects, but may even be essential to business survival.

Many studies have shown that eliminating disparities in health outcomes could yield vast economic and social benefits in terms of lower health-care costs, longer and healthier lives, and increased productivity and living standards. Increasingly payers, providers, and other participants in the health-care system agree that promoting health equity is a critically important goal. Yet because it can be difficult to prove that health equity initiatives will deliver a positive return on investment (ROI) to the organizations undertaking them, many promising initiatives go unfunded.

Some health equity advocates suggest that health-care organizations should set aside considerations of ROI altogether and address health equity out of a sense of social obligation. While this argument has an undeniable moral appeal, it alone is unlikely to persuade most organizations to make large-scale investments in health equity. There also needs to be a compelling business case for doing so.

Fortunately, there is one. To make the case, however, health-care organizations will need to move beyond standard ROI analysis, which is both too focused on the near term and too narrow in scope to capture the full benefits of investing in health equity, and adopt an expanded ROI framework. Rather than the typical one-year time horizon, this framework would evaluate ROI over a longer time horizon of perhaps three to five years. In addition to the direct impact of health equity investments on health-care revenues and expenditures, it would take into account the indirect returns to these investments, from enhanced brand appeal to improved employee engagement and productivity. It would also take into account the strategic advantages that can flow from promoting health equity in an America where the population is becoming more diverse, the society is becoming more aware of and committed to addressing health inequities, and the health-care system is inexorably moving toward value-based care (VBC) models.

While adopting this expanded framework would represent a major departure in how most health-care organizations evaluate the ROI of health equity initiatives, it is a framework that they already routinely apply to many other aspects of their business. Virtually no organization requires its HR, marketing, or legal departments to prove that all of their activities generate direct financial ROI, and certainly not over a one-year time horizon. Yet the activities of these departments are considered to be essential to long-term business success. So is investing in health equity.

The next section discusses the limitations of standard ROI analysis, while the following one summarizes our thinking on what an expanded framework for evaluating ROI might look like. The final section then briefly sums up our main conclusion, which is that investing in health equity is not only good for society, but also good for business.

Three Critical Limitations

As applied to health equity, ROI analysis usually focuses on the direct impact of investments on health-care revenues and expenditures. Although the prospect of direct financial benefits is not the only consideration in assessing whether health equity initiatives are worth pursuing, it is the most important one, and as such often determines whether a particular initiative is launched or not.

For payers, a health equity initiative would be deemed to have a positive ROI if the cost of the initiative is expected to be less than the resulting savings in health-care expenditures from, for example, fewer preventable illnesses, more cost-effective management of chronic conditions, or reductions in inappropriate utilization, such as ER visits for noncritical care. It would also be deemed to have a positive ROI if the cost of the initiative is expected to be less than the resulting increase in revenues from, for example, greater membership growth.

For providers, the form that ROI takes depends on the type of payment arrangement in force. In fee-for-service (FFS) arrangements, it would show up in increased revenue due to improved patient engagement, and hence increased utilization, as well, perhaps, as to improved patient retention. In VBC arrangements, it would show up in larger quality bonuses due to better patient outcomes. In full-risk contract arrangements, it would show up in a lower total cost of care for covered lives.

While standard ROI analysis can be valuable, it has three critical limitations when applied to health equity initiatives. The first arises from the complexity of the economic, social, and environmental drivers of disparate health outcomes. In clinical trials, where most variables can be controlled for, it is relatively straightforward to isolate the impact of a single intervention, whether it’s a new drug or a new medical procedure. It is more difficult to isolate the impact of introducing a transportation benefit, a mobile health unit, or a food as medicine program in an underserved community, especially when more than one initiative may be in play at once. It’s a bit like asking: What did the most to improve my diabetes—the changes I made in my diet, my exercise habits, or my medications? The answer is likely to be all of the above.

The second limitation is that, even when positive ROI can be proved, it may not kick in over the one-year time horizon that most health-care organizations use in budget planning. New initiatives may take time to reach critical mass, individual behavior may take time to change, and trust in the health-care system may take time to build. No one expects to earn a positive return on the first year of tuition at a four-year college. Indeed, if you drop out after freshman year, your ROI will almost certainly be negative. You have to stay the course to enjoy the benefits. The same is true of investments in health equity.

Finally, standard ROI analysis typically ignores the indirect benefits, from enhanced brand appeal to improved employee engagement and productivity, that can accrue to health-care organizations from investing in health equity. Nor does it give any consideration to the strategic benefits that can flow from investing in health equity as America’s demographic, social, and health-care landscape evolves.

These limitations mean that standard ROI analysis can be more of an obstacle than an aid to sound business practice. It is one of the main reasons that health-care organizations fail to undertake many worthwhile initiatives that would not only improve health equity, but would also improve their own long-term financial health. And, because it prioritizes near-term over long-term returns, it is also one of the main reasons that many of the pilot projects which do get launched fail to achieve scale, have limited impact, and may be abandoned.

An Expanded Framework

There is a compelling business case for investing in health equity, but making it will require health-care organizations to adopt an expanded framework for evaluating ROI that better captures the full benefits. (See figure 1.)

To begin with, this framework would evaluate ROI over a longer timeframe of perhaps three to five years. This does not mean that health-care organizations would necessarily have to wait that long to determine whether an initiative is meeting their ROI expectations. Interim reviews could and should be made annually, or even quarterly, to assess whether milestones are being met. What it does mean is that initiatives would not be ruled out simply because they cannot deliver an immediate return.

In addition, the enhanced framework would take into account the indirect benefits of investing in health equity. Although these benefits are to some extent qualitative, they also involve positive feedback loops that can result in additional financial ROI. We have identified five areas where such feedback loops exist:

- Brand Appeal. Investing in health equity can enhance a health-care organization’s reputation in underserved communities. When an organization becomes known for reducing barriers to access, providing culturally sensitive care, and addressing unmet needs, it builds trust. Greater trust in turn can lead to greater member retention and growth for insurers and greater patient retention and growth for providers.

- Partnership Opportunities. Enhanced reputation can also facilitate partnerships with community-based organizations, and these partnerships in turn can improve the effectiveness of health equity initiatives, generating additional financial ROI. At the same time, a reputation for promoting health equity can be key to helping health-care organizations secure grants from government agencies and private foundations.

- Community Health. Investing in the health of communities can have wide-ranging economic and social benefits, including, over time, rising educational attainment, higher incomes, and greater stability. Some of these benefits will accrue to the health-care organizations making the investments. A healthier and more prosperous community, for instance, also means a deeper talent pool from which organizations will be able to draw in their capacity as employers.

- Employee Engagement. A health-care organization’s commitment to social impact is important to its employees, and can play a pivotal role in meeting hiring and retention goals. More generally, job satisfaction improves when employees feel that they are helping to advance an important mission. Organizations that invest in health equity will thus enjoy a comparative advantage in what is likely to remain a tight labor market.

- Employee Productivity. While most health equity investments are directed at improving the health of plan members, patients, or the broader community, some may target an organization’s own employees. A healthier workforce is a more productive workforce, with less absenteeism and less “presenteeism.” This too constitutes a comparative advantage that can generate financial ROI.

Finally, an expanded framework should take into account the strategic benefits of investing in health equity. America is changing, and as it does a commitment to promoting health equity will not only improve future business prospects, but may even be essential to business survival. We have identified three fundamental shifts that are making it increasingly important for health-care organizations to invest in health equity:

- Growing Population Diversity. Minorities already constitute a majority of children under the age of 18 in America. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that by 2045 they will constitute a majority of the total population. Health-care organizations with a strong commitment to promoting health equity will be better positioned for business success in an increasingly diverse America.

- Greater Issue Awareness. The pandemic, which took a greater toll among Blacks and Hispanics than non-Hispanic Whites, laid bare longstanding health inequities in America. Civil society is increasingly focused on addressing these inequities. With CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure vowing that health equity will “serve as the lens through which we view all of our work,” so is government. Health-care organizations with a strong commitment to promoting health equity will be better positioned for business success in an America that has finally woken up to the problem.

- The Rise of Value-Based Care. The whole health-care system appears to be moving inexorably toward VBC payment arrangements, and it is entirely possible that CMS will eventually make them mandatory in Medicare, Medicaid, and other government health programs. Although investments in health equity can generate financial ROI in FFS payment arrangements, the returns are potentially much larger in VBC arrangements. Health-care organizations with a strong commitment to promoting health equity will be better positioned for business success as America’s health-care financing environment continues to evolve.

No Conflict

None of this is meant to imply that health equity investments should be made haphazardly. Every initiative a health-care organization undertakes should have a clear rationale, be supported by rigorous analysis, and have concrete objectives toward which progress can be measured and tracked over time. Yet by the same token, holding health equity investments hostage to a narrow and near-term definition of ROI risks leaving unfunded many worthwhile initiatives that would not only improve health equity, but in the long run would also improve the bottom line.

Adopting an expanded ROI framework is a necessary step in building a successful health equity investment program, but it is not the only step. For many health-care organizations, investing in health equity is a new endeavor, and they may not have the requisite budgeting, risk management, planning, and operational capabilities to pursue it effectively. To acquire those capabilities, each organization will have to embark on a unique journey that will be shaped by its regional markets, consumer dynamics, and internal organizational culture. Yet if each journey will be unique, there are also certain common milestones that every organization will have to reach along the way.

We will discuss those milestones in the next issue of Health Equity Strategies. Here we simply close by underscoring the critical fact that both justifies and enables the journey. Contrary to what is often assumed, there is no inherent conflict between the moral imperative of promoting health equity and the financial imperative of ensuring that business investments generate positive financial returns. In fact, the two imperatives reinforce each other, which is why investing in health equity is and will always be good business.

How Biased Utilization Data Perpetuate Health Inequity: A Two-Part Strategy to Address the Problem

How Biased Utilization Data Perpetuate Health Inequity: A Two-Part Strategy to Address the Problem

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern