The Coming Global Demographic Transformation

Vantage Point: Mini Briefs from The Terry Group and the Global Aging Institute

September 26, 2024

The latest UN population projections reveal a world on the cusp of a stunning demographic transformation. The global baby bust continues to deepen, countries almost everywhere are aging, and a growing number face long-term demographic decline. In this Vantage Point, we discuss the coming global demographic transformation, as well as the daunting social, economic, and geopolitical challenges it poses.

The UN Population Division’s latest biennial global population projections, released over the summer, reveal a world on the cusp of a stunning demographic transformation. Although populations in parts of the world are still young and growing, populations in most of it will soon be old and stagnant or contracting. The global baby bust continues to deepen, countries almost everywhere are aging, and a growing number face long-term demographic decline.

Demography may not be destiny, but it can and will profoundly reshape the world we live in. The release of the new UN projections provides a useful opportunity to examine the scope of the coming demographic transformation, as well as to reflect on the daunting social, economic, and geopolitical challenges it poses.

The Two Forces Driving the Transformation

The place to start is with the forces driving the demographic transformation. There are of course two, the first of which is rising life expectancy. People are living longer, and this increases the relative number of old in the population.

Worldwide, life expectancy at birth has risen by fifteen years over the past half century, from 58 in 1975 to 73 in 2023.1 In most developed countries life expectancy is now in the early eighties, and in some emerging markets it is as high or nearly as high. In Mexico and Bangladesh life expectancy is 75, in Malaysia and Turkey it is 77, in China and Iran it is 78, in Saudi Arabia it is 79, and in Chile it is 81.

The second force driving the demographic transformation is falling fertility. People are having fewer babies, and this decreases the relative number of young in the population. Although rising life expectancy may be what first leaps to mind when most people think of population aging, falling fertility is quantitatively an even more important driver.

Birthrates have always plunged in times of war, famine, or pestilence. Today, for the first time in recorded history, societies that are both peaceful and prosperous are failing to reproduce themselves. In every developed country, with the single exception of Israel, the total fertility rate (TFR), a measure of average lifetime births per woman, has fallen beneath the so-called 2.1 replacement rate needed to maintain a stable population from one generation to the next. Most developed countries have been beneath the replacement rate for decades, and many are far beneath it. In the United States the TFR is now 1.6, in Western Europe it averages 1.5, in Japan it is 1.2, and in South Korea it is just 0.7.

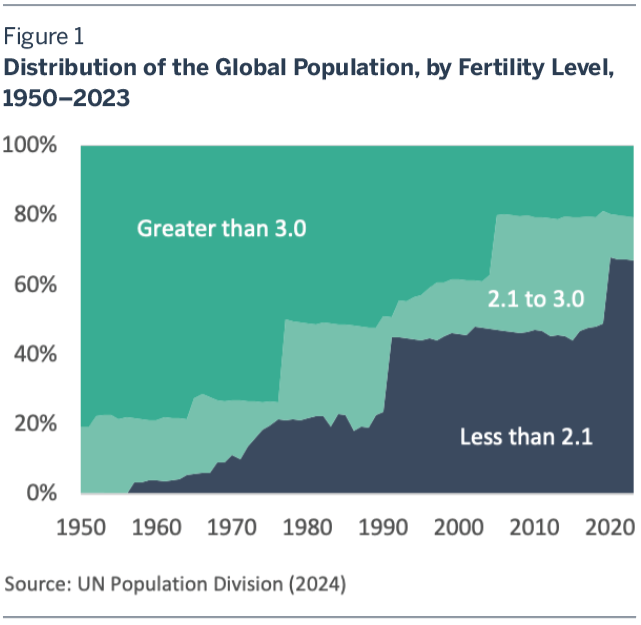

The trend toward smaller family size began in the rich world, but it has now overtaken most of the emerging world as well. Since 1975, the TFR in South Asia has fallen from 5.5 to 2.2. In Latin America it has fallen from 4.6 to 1.8, and in East Asia it has fallen from 3.3 to 1.0, less than half of the rate needed to replace the population. In 1975, just 20 percent of the world’s population lived in countries with below-replacement fertility rates, almost all of them in Europe. By 2000, that share had risen to 46 percent. As of 2023 it stood at 67 percent. (See figure 1.)

Neither of these trends is likely to be reversed anytime soon. Improvements in public health, breakthroughs in biomedicine, and healthier lifestyles still have considerable potential to push up life expectancy. Although experts disagree on how much further it can rise, few believe that we are yet approaching the limit. In 1975, no country in the world had a life expectancy of 80 or more. Today, roughly fifty do. By 2075, the UN projects that there will be roughly one hundred and fifty.

As for fertility, the factors weighing it down are many and varied. They include declining religiosity, rising educational attainment, especially of women, the widespread availability of effective contraception, the growing cost of childrearing, and the difficulty that young adults in many countries face in launching careers and establishing independent households.

Low fertility may also be self-perpetuating. When birthrates are high, young adults see their friends, neighbors, and colleagues having children, and this sends a social signal that family formation is normal, even expected. When birthrates are low, and have been low for decades, having a small family or no family becomes the new social norm. Demographers call this dynamic the “low-fertility trap.”2

The dynamic helps to explain why even generous pronatal incentives rarely have much effect in low-fertility countries. South Korea is a case in point. In recent years, its government has enacted numerous measures designed to boost birthrates, including monthly cash allowances for parents with young children, paid maternity and paternity leave, and subsidized daycare. Yet its fertility rate continues to plumb new lows. (See “Lessons from South Korea’s Fertility Freefall,” March 27, 2024.)

Population Aging and Population Decline

Put these two trends together, and what you get is a dramatic aging of the population. For most of human history, the elderly made up only a tiny fraction of the population—never more than 5 percent in any country until well into the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century. The age structure of every country’s population resembled a pyramid, with lots of children at the base and a small number of elderly at the top.

In many countries that population pyramid has come to resemble a column, and in a growing number the pyramid is beginning to invert. In the developed world, the UN projects that the elderly share of the population, now 20 percent, will rise to 27 percent by 2050 and to 29 percent by 2075. In some faster-aging developed countries like Italy, Japan, and South Korea, the elderly share of the population could by then be approaching or even passing 40 percent.

The aging trend in many emerging markets is even more dramatic, not because their populations will grow older than those in the developed world but because they are aging much faster. As recently as 1990, when the elderly share of the developed world’s population was already 12 percent, the elderly share of China’s population was just 5 percent. Today it is 14 percent, and by 2075 the UN projects that it will reach 42 percent. The elderly share of Mexico’s population, which is still just 8 percent today, is projected to climb to 26 percent by 2075. Iran’s, which is also just 8 percent today, is projected to climb to 31 percent, while Thailand’s, which is 15 percent today, is projected to climb to 35 percent.

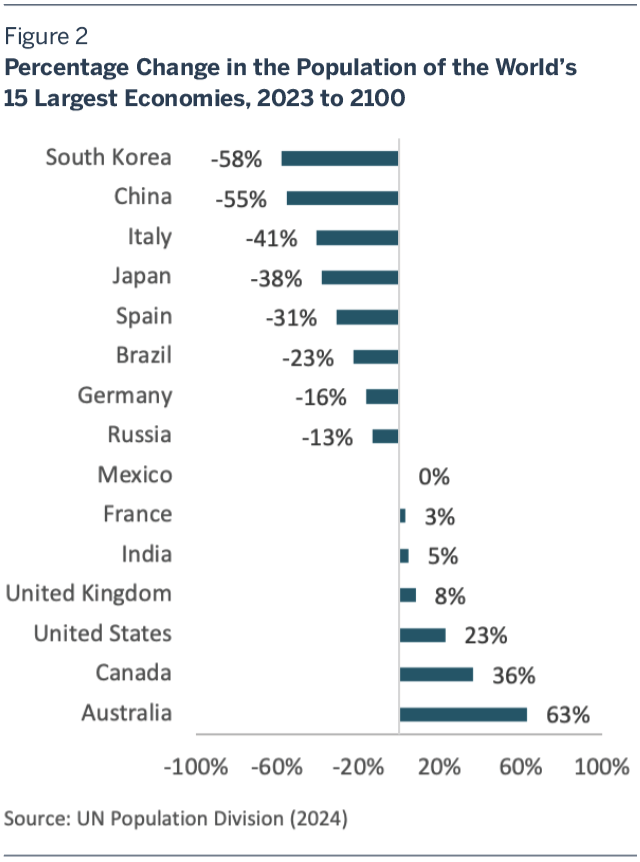

Along with population aging, there is a second and closely related dimension of the demographic transformation. Falling fertility is not only hollowing out the base of the traditional population pyramid, leaving it top-heavy with elderly, it is also ushering in a new era of widespread population decline. Among the world’s fifteen largest economies, only Australia, Canada, and the United States will experience any appreciable population growth over the rest of the century. In some of the world’s largest economies, the cumulative population decline will be enormous. By 2100, the UN projects that there will be 31 percent fewer Spaniards than there are today, 38 percent fewer Japanese, 41 percent fewer Italians, 55 percent fewer Chinese, and 58 percent fewer South Koreans. (See figure 2.)

An Unrecognizable Demographic Landscape

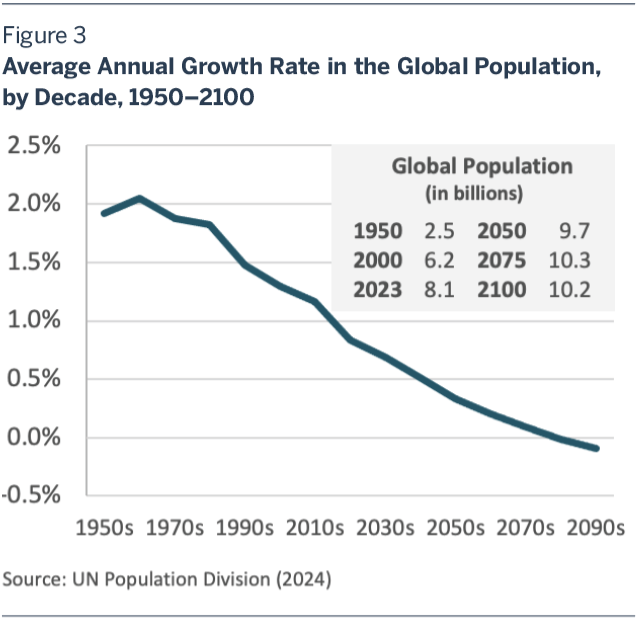

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, rapid population growth prompted worries that a teeming humanity would soon be falling off the edges of all seven continents. As birthrates have collapsed, the threat of a global Malthusian crisis has receded. The growth rate in the world’s population has by now been decelerating for decades and, according to the UN, will fall to zero by the 2080s. (See figure 3.) The world’s population will then peak and begin to decline. (See “Why the World Is Approaching Peak Population,” December 8, 2022.)

With most of the world’s population already living in countries with below-replacement fertility, readers may wonder why the world’s population hasn’t already peaked. There are two reasons, the first of which involves what population experts call “demographic momentum.” From Brazil to India, many populous countries that now have below-replacement fertility rates had very high fertility rates a generation ago, which means that very large cohorts of women are now passing through their childbearing years. As a result, even though these women are having many fewer children than their mothers did, the population will continue to grow, at least for a while.

The second and more important reason is that there are some places in the world where fertility rates, though falling, still remain very high. In sub-Saharan Africa, the TFR now averages 4.3—a lot lower than the 6.8 it averaged in 1975, but still far above the replacement rate. A scattering of countries in the Greater Middle East, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Yemen, also have fertility rates that remain far above replacement.

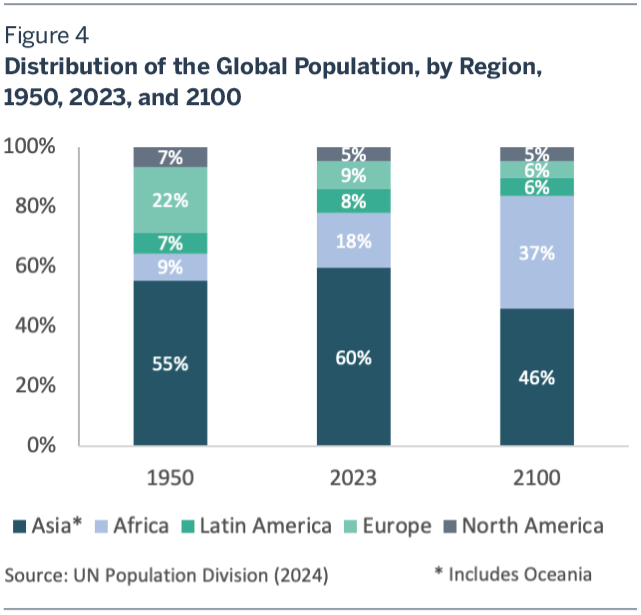

The persistence of high fertility in these places will not only delay the date that the world reaches peak population, but will also lead to an enormous shift in the distribution of the global population. Since 1950, Asia has accounted for three-fifths of total global population growth. By 2050, Asia will be accounting for none of it and Africa will be accounting for more than all of it. In 1950, the population of Europe was more than twice as large as Africa’s. By 2100, the UN projects that Africa’s population will be more than six times larger than Europe’s. Along the way, the global demographic landscape will be transformed beyond recognition. (See figure 4.)

Daunting Challenges

While the threat of a global Malthusian crisis may have receded, the emerging new demographic realities pose challenges that are every bit as daunting.

To begin with, economic growth will slow in an aging world. Falling fertility translates into slower growth in the working-age population, which in turn translates into slower growth in employment and GDP. In the United States, growth in the working-age population will fall to near zero in the coming decades, even assuming a substantial ongoing influx of immigrants. In some faster-aging countries, including China, Germany, Italy, and Japan, working-age populations will soon be contracting by between 1 and 2 percent per year. Unless productivity rises at least as fast as employment falls, they will face a future of secular stagnation—that is, no growth in real GDP across the business cycle, from peak to peak and trough to trough.

Unfortunately, population aging is more likely to pull down than to push up productivity growth. As workforces grow more slowly or contract, societies are likely to invest less. Workforces will also be aging, and aging workforces may be less mobile, less flexible, and less entrepreneurial. In this environment, governments may be tempted to double down on protectionist policies in a bid to prop up flagging living standards. If so, they will only exacerbate the problem. Both advanced economies and emerging markets would suffer, but emerging markets, which may find themselves caught in a permanent “middle-income trap,” would suffer the most.

Even as economic growth slows, old-age dependency burdens will rise. In today’s developed countries, the challenge will be largely fiscal. Graying means that governments will need to pay more for pensions, more for health care, and more for long-term care for the frail elderly. With aging electorates likely to resist cuts in old-age benefits, taxes on current workers are bound to rise, national debts to grow, or both. The result may be even slower economic growth.

While today’s developed countries became affluent societies before they became aging societies, today’s emerging markets are aging while they are still in the midst of development and before they have put in place the full social protections of a modern welfare state. In emerging markets from India and Indonesia to Mexico and Brazil, only a fraction of the workforce is covered by a formal retirement system of any kind, public or private. Inevitably, much of the rising old-age dependency burden will fall on the extended family. Yet traditional family support networks are already under stress from the forces of modernization, and will soon come under intense new demographic pressure from declining family size. A humanitarian aging crisis of colossal proportions may loom in the future of some emerging markets.

Then there is the growing risk of demographically driven social and political instability. Many of those countries that still have high fertility rates and fast-growing populations suffer from poor governance, limited institutional capacity, and deep-seated ethnic and religious divisions. Rather than being an asset, their youthful demographics could be a liability. Many of these countries may struggle to invest adequately in infrastructure and human capital, fail to create productive jobs for the rising generation, and find themselves mired in poverty and prey to social unrest, civil strife, and state failure.

Meanwhile, population aging and population decline could exacerbate the risk of great power conflict. Some scholars have argued that demographic trends are pushing today’s great powers toward a “geriatric peace” in which all of the potential belligerents will be too enfeebled to wage war.3 As a long-term proposition, this argument has some merit. In the near term, however, today’s geopolitical rivals are likely to respond to emerging demographic trends in very different ways. Liberal democracies may be content to peacefully age, but authoritarian regimes, contemplating a future of demographic and economic decline, may instead be tempted to challenge today’s rules-based world order while they are still able to do so. (See “Can an Aging China Still Be a Rising China,” July 26, 2023.)

Overcoming these challenges will be much easier if the world remains interconnected. Open global labor markets can match workers in younger and faster-growing countries with job opportunities in older and more slowly growing or contracting ones. Open global capital markets can similarly match savers in countries where capital is abundant and labor is scarce with investment opportunities in countries where the opposite conditions prevail. Ensuring that the world remains interconnected, moreover, would not only reduce the economic costs of population aging and population decline, but could also reduce the geopolitical risks. Unfortunately, the world now seems to be moving in the opposite direction.