The Health Equity Journey

Health Equity Strategies No. 4

January 18, 2023

Key Learnings

- Health-care organizations are increasingly focused on improving health equity. Yet for many of these organizations, investing in health equity is a new endeavor that poses a whole new set of planning, budgeting, and operational challenges.

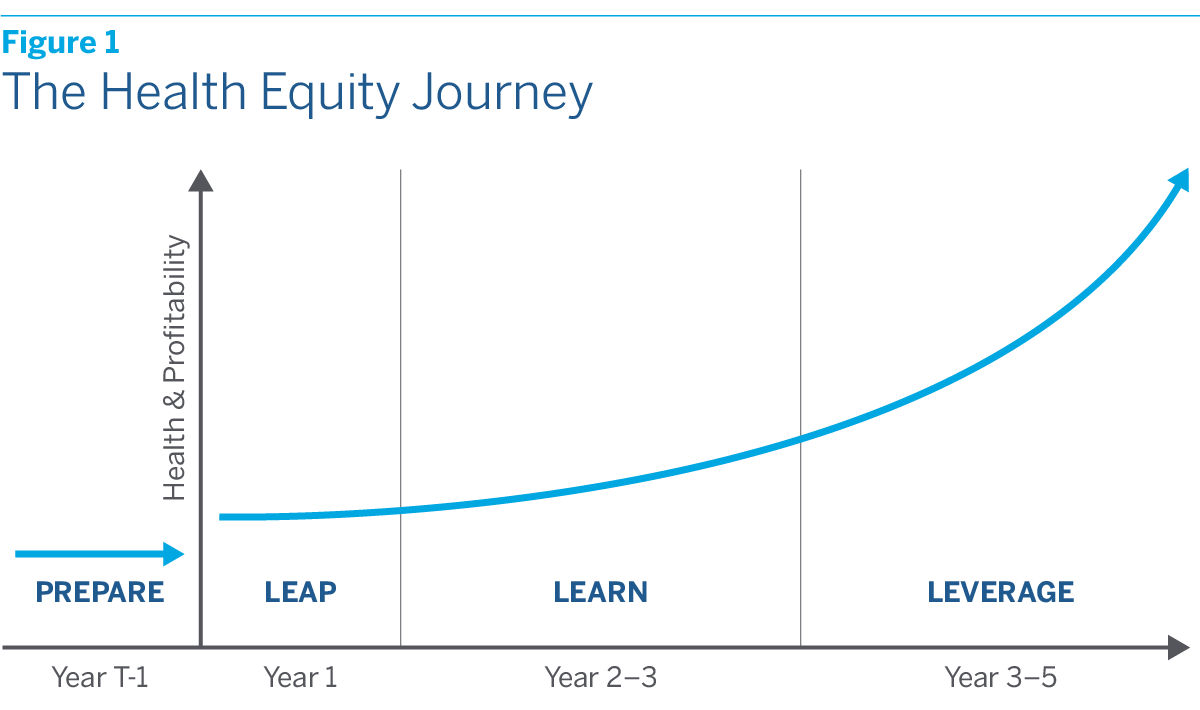

- In this issue of Health Equity Strategies, we offer a high-level guide to the health equity journey, which can be usefully divided into three stages that we call the “Three L’s.” The first L stands for “leap.” In this stage, the organization launches one or more pilot projects designed to address unmet health needs in the community. The second L stands for “learn.” In this stage, data are collected and analyzed, pilot projects are refined, and business systems are standardized. The third L stands for “leverage.” In this stage, successful pilot projects are scaled up by extending them to larger populations and/or new geographies.

- The potential payoffs of investing in health equity are large. There is of course the satisfaction of knowing that lives have been improved and injustices redressed. But along with this satisfaction, there will also be tangible business benefits in an America that is becoming more diverse, is increasingly focused on eliminating health disparities, and in which the health-care system itself is moving inexorably toward VBC payment arrangements.

Over the past few years, health equity has become the object of intense new attention. Spurred in part by the pandemic, which laid bare the vast human cost of remediable health disparities, both civil society and government are increasingly focused on improving health equity. So are health-care organizations themselves, many of which are launching or planning to launch new health equity initiatives.

For many of these organizations, investing in health equity is a new endeavor that poses a whole new set of planning, budgeting, and operational challenges. As each organization proceeds, it will be embarking on a unique journey that will be shaped by its regional markets, consumer dynamics, and internal culture. Yet if each journey will be unique, there are also common milestones that every organization will have to pass along the way.

In this issue of Health Equity Strategies, we offer a high-level guide to the health equity journey that we have distilled from our client work. We begin with the essential preparations for the journey, which include identifying opportunities and setting goals, forging partnerships, putting in place an expanded framework for measuring return on investment (ROI) that captures the full benefits of investing in health equity, and ensuring that the organization’s analytic capabilities are up to the task of interpreting results and measuring progress over time.

We next turn to the journey itself, which can be usefully divided into three stages that we call the “Three L’s.” The first L stands for “leap.” In this stage, the organization launches one or more pilot projects designed to address unmet health needs in the community. The second L stands for “learn.” In this stage, data are collected and analyzed, pilot projects are refined, and business systems are standardized. The third L stands for “leverage.” In this stage, successful pilot projects are scaled up by extending them to larger populations and/or new geographies. Progressing from stage one to three will normally take three to five years. (See figure 1.)

We then conclude with a brief discussion of pitfalls that must be avoided along the way, as well as the payoffs that await at journey’s end.

Preparing for the Journey

Successful journeys require adequate preparation, especially when the terrain to be traversed is unfamiliar and challenging. Before an organization attempts to launch a health equity investment program, it will need to take a series of essential preparatory steps.

- Identify opportunities and set goals. As with any business venture, the place to start is to identify opportunities and set goals. No health-care organization can hope to eliminate all disparities in health outcomes, since their root causes lie in broader economic, social, and cultural realities over which health-care system participants have little control. Yet when properly designed, health equity initiatives can make a real difference, whether it’s by overcoming obstacles to access by offering transportation and childcare benefits, closing bias-related gaps in care with culturally and linguistically tailored engagement programs, or improving nutrition through food as medicine programs. The initiatives that organizations develop should both be based on an assessment of unmet needs in the community and build on proven strengths of the organization itself. They should also include concrete goals toward which progress can be measured.

- Forge external partnerships. Successfully carrying out most health equity initiatives will require forging ongoing relationships with external partners. These partners may include nonprofit foundations, which can collaborate in designing the initiatives, as well as provide funding. They will almost certainly include NGOs operating in the community, as well as other community actors ranging from childcare providers to pharmacies and food delivery services. All of these partners will need to be carefully vetted to ensure not only that they possess the relevant capabilities, but also that they are trusted in the community.

- Forge internal partnerships. At least initially, health equity initiatives will need to lean heavily on the resources and capabilities of the rest of the organization, including existing personnel, operational systems, and digital platforms. Although health equity investment programs may ultimately develop into their own “business lines,” they will never get off the ground without internal cooperation. It is therefore critical to ensure in advance that this will be forthcoming. It will also be helpful if the organization as a whole is moving in a direction that fosters synergies. If an organization is already moving toward value-based care (VBC) payment arrangements, for instance, health equity initiatives will benefit from the “adjacent momentum.”

- Put in place an expanded ROI framework. Standard ROI analysis is too focused on the near term and too narrow in scope to capture the full benefits of investing in health equity. It is one of the main reasons that health-care organizations fail to undertake many worthwhile initiatives that would not only improve health equity but also their own bottom line. Because it prioritizes near-term over long-term returns, it is also one of the main reasons that many of the pilot projects which do get launched fail to achieve scale, have limited impact, and are abandoned.As we argued in the last issue of Health Equity Strategies (“The Business Case for Investing in Health Equity,” August 11, 2022), an expanded ROI framework is needed. This framework would evaluate the ROI of health equity investments over a longer time horizon of three to five years. Along with direct returns, it would take into account the indirect returns to health equity investments, from enhanced brand appeal to improved employee engagement and productivity. It would also consider the strategic advantages of promoting health equity in an increasingly diverse America that is becoming more aware of and more committed to addressing health inequities.

- Review and if necessary upgrade analytic capabilities. Navigating the health equity journey will require robust analytic capabilities. At the outset, organizations will need to analyze existing internal and external data, including data on Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), in order to determine which types of initiatives are the most promising. Along the way, they will need to collect and analyze new data related to the initiatives they have launched in order to determine whether health and ROI milestones are being met. Before beginning the journey, organizations should review their analytic capabilities and if necessary upgrade them, perhaps by hiring new internal talent or engaging external talent.

The Three L’s

While careful planning and preparation can help to ensure that the health equity journey is a successful one, it is impossible to anticipate all of the bumps, ruts, and turns in the road ahead. The journey itself will necessarily involve surprises. Organizations will therefore need to engage in a continuous process of evaluation, adjustment, and perhaps even redirection over the course of its three stages, from leap to learn to leverage.

- LEAP (Year 1). The journey begins with the launch of one or more pilot projects. Inevitably, this launch will involve a leap of faith, though it need not be an uninformed one. Existing data, including both internal data on members and patients and external SDOH data, can help organizations identify those populations and communities that are most likely to be underserved by the health-care system, as well as the types of interventions most likely to improve engagement and outcomes. Based on this data, as well as observation and experience, they can then design and implement a wide variety of initiatives that could potentially have a large impact on health equity.Among the possibilities are setting up clinics at community centers; deploying mobile health units; creating training programs for community health workers and patient navigators; initiating food as medicine programs; and offering nonmedical benefits like transportation and childcare.The first stage of the health equity journey lasts about a year. During it, initiatives will need to rely on the organization’s existing resources and capabilities for everything from staff to digital platforms, even if these are not a perfect fit. The advantage of this arrangement for the health equity initiatives is that it minimizes initial investment needs and allows rollout to proceed more quickly. The advantage for the organization as a whole is that it may generate additional marginal revenue at little or no additional cost.

- LEARN (Year 2 to 3). While learning of course begins the moment that a pilot project is launched, it accelerates once organizations have collected and analyzed sufficient project data to determine what is working and what isn’t. This threshold will normally be reached by the second year of the health equity journey.During this learning stage, organizations will be able to refine their pilot projects to better meet the needs of members and patients—or if only one project was launched initially, to launch complementary ones with greater confidence of success. Even as they learn more about the demand side, organizations will also learn more about how to efficiently manage the supply side, thereby reducing unit costs. Along the way, their personnel needs will become clear, allowing them to staff up. So will their IT needs, allowing them to tech up and customize their digital platforms.To further refine their pilot projects, organizations may wish to conduct member and patient surveys designed to identify “sustainable pathways” through which behavior and hence health outcomes can be influenced. The surveys would focus on questions that cannot be answered, or at least not fully answered, by data on the demographic or socioeconomic group to which people belong or the community in which they live. We have in mind such things as people’s attitudes toward the health-care system, the access limitations they face, their engagement preferences, and their degree of health awareness.

By the end of the third year of the health equity journey, organizations should be in a position to determine which pilot projects have moved the needle on health equity—and, just as importantly, which are delivering, or at least are on track to deliver, a positive ROI.

- LEVERAGE (Year 3 to 5). The final stage of the health equity journey, which will normally begin in its third or fourth year, is all about leverage. During this stage, organizations should close down unsuccessful pilot projects and scale up successful ones to larger populations and/or new geographies. By this point, the fixed costs incurred in launching successful projects will likely have been recouped, allowing profits to fund additional growth. Operational systems, job descriptions, and digital platforms should also have been standardized. In short, health equity investment programs will have developed into their own sustainable business lines.

Pitfalls and Payoffs

There is of course no guarantee that the health equity journey will be a smooth one. To navigate it successfully from start to finish, organizations will have to avoid many pitfalls. They will need to take care in their choice of external partners, whose core capabilities should complement rather than compete with the organization’s own. They will need to resist the temptation to jump to the leverage stage too soon. It takes time to know with any confidence which pilot projects are worth scaling up and which should be closed down. In making these choices, moreover, organizations will need to be guided by the cold calculus of return on investment. Just because a project is well intentioned doesn’t mean that it is sustainable or scalable.

Finally, organizations will need to accept that they cannot be all things to all people. While it may be advisable to start out with an array of pilot projects that addresses a broad spectrum of needs, once organizations have discovered what they are best at they should specialize. If they try to do everything possible to advance health equity, they may end up doing nothing well.

Yet if the pitfalls are many, the potential payoffs are large. There is of course the satisfaction of knowing that lives have been improved and injustices redressed. But along with this satisfaction, there are also tangible business benefits. To begin with, there is the direct financial ROI to pilot projects that are successfully scaled. Then there are the indirect benefits that can flow from enhanced brand appeal and improved employee engagement and productivity, which over time may translate into additional direct financial ROI. Above all, there are the strategic benefits of promoting health equity in an America that is becoming more diverse, is increasingly focused on eliminating health disparities, and in which the health-care system itself is moving inexorably toward VBC payment arrangements. CMS has just rolled out a new Accountable Care Organization model (ACO REACH) that explicitly incorporates health equity goals.

While the health equity journey inevitably entails risks, these risks are not as great as those that organizations will ultimately face if they fail to undertake the journey at all. Committing to a program of health equity investment is not just a question of social responsibility. In the long run, it may be essential for business survival.

The Business Case for Investing in Health Equity

The Business Case for Investing in Health Equity

How Biased Utilization Data Perpetuate Health Inequity: A Two-Part Strategy to Address the Problem

How Biased Utilization Data Perpetuate Health Inequity: A Two-Part Strategy to Address the Problem

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern

A New Way to Think about Health Equity: Understanding Spheres of Influence and Concern